“È sempre lo stesso mondo che mi interessa. Quel mondo che non siamo stati capaci di capire quando era il momento giusto e che forse capiremo quando è troppo tardi” (Mario Giacomelli)

Il tempo fotografico è sempre stato e sempre sarà un tempo illusorio.

Sembra proprio che Salvador Dalì avesse colto perfino questa curiosa angolazione, distorcendone gli elementi, con i suoi orologi molli o fusi…

English versionMa il tempo fotografico è illusorio non solo perché costringe un attimo di vita ad una permanenza irrealisticamente irripetibile, o perfino presunta, ma anche perché la sospensione che la fotografia induce nell’ottica temporale non riguarda solo il tempo successivo allo scatto ma anche, e soprattutto, il tempo antecedente. La foto, qualsiasi foto, anche se predeterminata, concepita, organizzata e programmata, vive nell’intenzione, si forma, si argomenta e definisce i propri limiti e le proprie linee compositive prima (a volte molto prima) del momento in cui tecnicamente viene realizzata.

Ma possiamo anche dire che che l’irruzione liberatoria dell’inconscio nella creazione artistica (letteraria e figurativa e musicale), d’altronde complica e riafferma proprio questo presupposto, celandolo nella possibile “impossibilità” che una determinata scena si possa prevedere o programmare, oppure privilegiando la prevalenza del caso nell’ordine delle cose, e di converso, di chi quel “caso”, quella fortuita combinazione sa attendere con enorme pazienza, giacchè questa enorme pazienza precede la sua motivazione cosciente, e da tempo (chissà quanto) naviga in un’intenzione profonda che quella casualità saprà prima ancora che cogliere, addirittura generare.

Dice il Conte Dracula, nella versione cinematografica di Francis Ford Coppola: “ho attraversato gli oceani del Tempo per trovarti”.

E allora l’Arte rende immortali, veramente, non solo per via di una celebrità, ma anche perchè il tempo brama finire (si sa) ma conosce le regole della redenzione e del compenso.

“Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi” è una raccolta di poesie di Cesare Pavese (1908-1950), pubblicata postuma. Comprende 10 poesie, tutte scritte nell’arco di un mese nel 1950, e ritrovate fortuitamente tra le sue carte dopo la sua morte. Rivolgendosi all’amante che l’ha abbandonato, e prima di salutare questa vita, Pavese incarica “gli oceani del tempo” di trascinare avanti un messaggio e affidarlo alle infinite soluzioni dell’Arte e della Poesia.

“Sei la vita e la morte./ Sei venuta di marzo/ sulla terra nuda -/ il tuo brivido dura./ Sangue di primavera/ – anemone o nube – / il tuo passo leggero/ ha violato la terra. / Ricomincia il dolore!”

Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000) è tra i più famosi e sicuramente tra i più grandi fotografi di tutti i tempi. Lavorò per tutta la vita nella Tipografia Marchigiana, a Senigallia, e si dedicò alla fotografia (e in gioventù anche alla pittura e alla poesia) soltanto nel tempo libero. Si racconta che per realizzare un singolo scatto fosse capace di recarsi alla stessa ora, giorno dopo giorno, nello stesso luogo, dove aveva pianificato la ripresa, in attesa che le condizioni ottimali di luce, aria, vento, ecc., si realizzassero coincidendo con la sua intenzione.

Ma in fondo sapeva che la Poesia (l’azione della Poesia) non è pianificabile, e quasi sempre finiva per scattare qualcosa che gli veniva in mente in quel preciso momento oppure se ne andava, dietro un nuovo progetto che un suono interiore aveva messo in movimento nella sua fantasia, e che magari si sarebbe attivato molto tempo cronologico dopo…

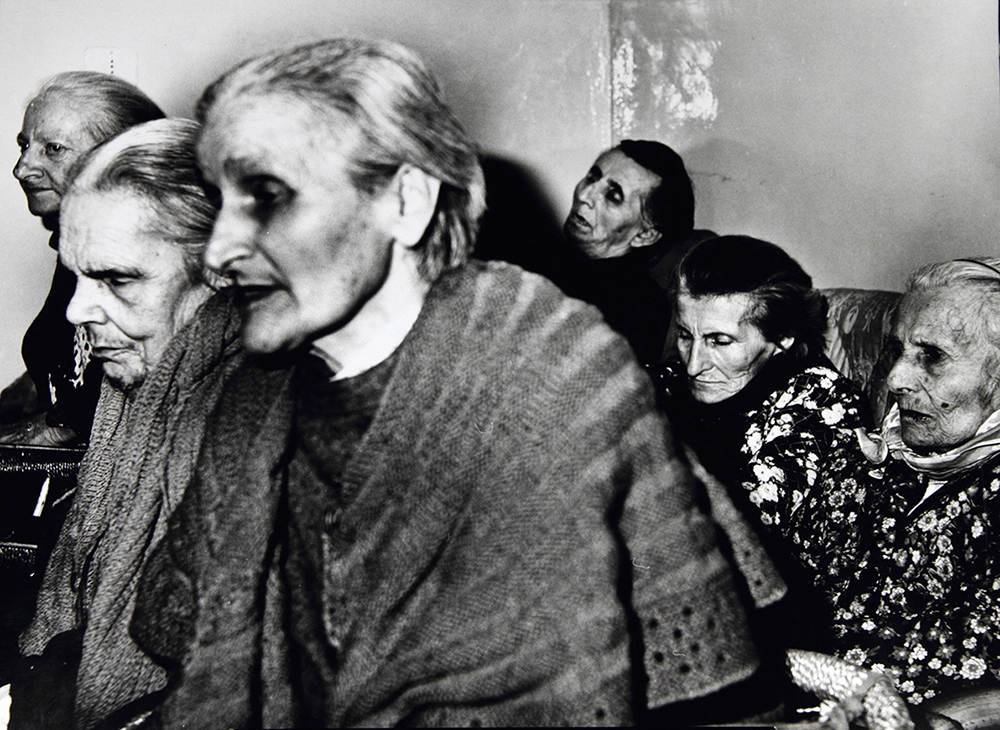

Tra il 1954 e il 1956 frequenta lungamente l’Ospizio di Senigallia, dove realizza una straordinaria, lacerante, e terribile, serie di fotografie che intitolerà proprio “Verrà la morte e avrà i tuoi occhi”.

“Sono andato lì per un anno, nell’ospizio di Senigallia, per ambientarmi, capire, e ho imparato molte cose, poi due anni per fotografare; le cose più importanti sono quelle che non sono riuscito a fotografare, quelle che però mi hanno dato di più. Per esempio c’è l’orario di ingresso, ed in tre anni una vecchietta quando entravano i parenti aspettava il figlio, e guardava ognuno che entrava per vedere se era lui e giustificava sempre il figlio dicendo: poverino, magari chissà quanto ha da lavorare; però in tre anni nessuno è mai andato a farle visita, e questo non potevo fotografarlo. … Dopo avere lottato tutta una vita, perché la fine di una vita deve essere questa? Normalmente si dice che la fotografia vale più di mille parole, ma questa realtà c’è così vicina che le fotografie e le parole perdono valore. Queste immagini sono più realiste anche nella tecnica, le più vere e le più essenziali. Perché più che quello che vedevo, volevo rendere quello che avevo dentro di me: la paura di invecchiare, non di morire, il disgusto per il prezzo da pagare per una vita”.

Il disgusto, la paura e la curiosità per il Tempo, i suoi orrori, la sua meraviglia…

Ma la vita, la morte, le sorgenti e le cantilene del Tempo, la carne e lo spirito, incrociano i loro sentieri nelle stesse regioni, e anche in musiche e fantasie, in ispirazioni di natura fantastica e squisitamente visionaria…

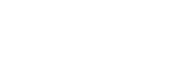

The Musical Box (1971), una delle canzoni più famose dei Genesis, è il brano d’apertura dell’album Nursery Cryme (assonanza della tipica filastrocca inglese per bambini Nursery Rhyme). Racconta sostanzialmente una storia di fantasmi in un’ambientazione decadente e vittoriana, ma sfiora anche molte delle diffrazioni e asimmetrie che il tempo induce nell’ispirazione artistica, accostando i temi della morte e quelli della reincarnazione e dell’amore sensuale.

Mentre un bambino di 8 anni (Henry Hamilton-Smythe) sta giocando a croquet con una sua amichetta (Cynthia Jane De Blaise-William, di 9 anni), quest’ultima lo decapita graziosamente con la sua mazza.

Ma Henry torna presto… Qualche giorno dopo il fatto, Cynthia entra nella camera di Henry e trova il carillon (Musical Box) del bambino, lo apre e mentre scorrono le note della filastrocca Old King Cole, lo spirito di Henry si materializza davanti alla piccola assassina. Ma – come Dracula ben sapeva, tanto da dover diventare vampiro per non subirne l’effetto – gli oceani del Tempo non si possono attraversare senza conseguenze…

Lo spirito di Henry comincia ad invecchiare rapidamente e, in breve, davanti a Cynthia si presenta un laido vecchio che esige dalla ragazzina soddisfazione sessuale, a compenso del danno provocato.

Ora, la canzone assume di colpo un andamento verticale, sempre più incalzante, le sonorità classicheggianti precedenti si incrociano e si sovrappongono al ruggire di note distorte di chitarra e di ritmica in crescendo, al di sopra delle quali la voce di Peter Gabriel vola, rauca e ossessiva, urlando più volte: “Why don’t you touch me??!!??”, che sarebbe l’ingiunzione-supplica di Henry a Cynthia. Ma proprio in quel momento la “nurse” di Henry entra nella stanza, vede il fantasma e gli scaglia addosso il carillon, distruggendo entrambi.

La musica, dopo il crescendo isterico, si placa in una conclusione di tipo classico, con le chitarre a giocare il ruolo tradizionale dei fiati.

E allora, l’oceano del tempo si ricompone, le sue onde riprendono a scorrere lievi, le immagini, le note, le parole si chiudono in altre epoche presenti, passate e future.

Resta solo la poesia.

Of some sailers in the oceans of time

“It is always the same world that interests me. That world that we have not been able to understand when it was the right time and that perhaps we will understand when it will be too late “(Mario Giacomelli)

The photographic time has always been and always will be an illusory time. It seems that Salvador Dali had even caught this curious angle, distorting the elements, with his soft or melted clocks …

But Photographic Time is illusory not only because it forces a moment of life to an unrealistic or even “presumed”, unrepeatability, but also because the suspension that photography induces in the temporal perspective does not only concern the time after shooting but also, and above all, the time before. The photo, any photo, even if predetermined, conceived, organized and programmed, lives in the intention, is formed, argues and defines its own limits and compositional lines before (sometimes much before) the moment in which “technically” is done.

But we can also say that the liberating irruption of the unconscious in artistic creation (literary and figurative and musical), on the other hand, complicates and reaffirms this assumption, concealing it in the possible “impossibility” that a given scene can be predicted or programmed, or by privileging the prevalence of chance in the order of things, and conversely, of those who “chance”, that fortuitous combination can wait with enormous patience, since this enormous patience precedes their conscious motivation, and for some time (who knows how much) in a profound intention that that randomness will know before even grasping, even generating.

Count Dracula, in the film version of Francis Ford Coppola, says: “I have crossed the oceans of Time to find you”.

And then Art makes “immortal”, really, not only because of a celebrity, but also because time longs to end (you know) but knows the rules of redemption and compensation.

“Death will come and will have your eyes” is a collection of poems by Cesare Pavese (1908-1950), published posthumously. It includes 10 poems, all written over a month in 1950, and accidentally found among his papers after his death. Addressing the lover who abandoned him, and before saying goodbye to this life, Pavese instructs “the oceans of time” to drag forward a message and entrust it to the infinite solutions of Art and Poetry.

“You are life and death. / You came in March / on the bare earth – / your shiver lasts. / Blood of

spring / – anemone or cloud – / your light step / has violated the earth. / Pain begins again! ”

Mario Giacomelli (1925-2000) is among the most famous and certainly among the greatest photographers of all times. He worked all his life in the “Tipografia Marchigiana”, in Senigallia, and devoted himself to photography (and in his youth also to painting and poetry) only in his spare time.

It is said that to achieve a single shot, Giacomelli was able to go to the same time, day after day, to the same place where he had planned the recovery, waiting for the optimal conditions of light, air, wind, etc., to be achieved by coinciding with his intention.

But in the end he knew that Poetry (the action of Poetry) cannot be planned, and almost always ended up taking something that came to his mind at that precise moment or he left, behind a new project that an internal sound had put into movement in his imagination., and that perhaps would have been activated a long chronological time “after” …

Between 1954 and 1956 he frequented the Hospice of Senigallia for a long time, where he made an extraordinary, lacerating, and terrible series of photographs which he would entitled “Death will come and will have your eyes”

“I went there for a year, in the Senigallia hospice, to settle down, understand, and I learned many things, then two years for taking photos; the most important things are those that I have not been able to photograph, but those that have given me more. For example, there is the time for visits, and in three years an old woman when relatives entered was waiting for her son, and looked at everyone who came in to see if it was him and always justified her son saying: poor baby, maybe who knows how long he has to work…. but in three years no one has ever gone to visit her, and this I could not photograph. … After having struggled a lifetime, why must this be the end of a life? Normally it is said that photography is worth more than a thousand words, but this reality is so close that photographs and words lose value. These images are more realistic even in technique, the truest and most essential. Because more than what I saw, I wanted to make what I had inside about me: the fear of getting old, not dying, the disgust for the price to pay for a lifetime “.

Disgust, fear and curiosity about Time, its horrors, its wonder …

But the life, death, springs and songs of Time, the flesh and the spirit, cross paths in the same regions, and also in music and fantasies, in inspirations of a fantastic and exquisitely visionary nature ..

“The Musical Box” (1971), one of the most famous songs of Genesis, is the opening song of the album “Nursery Cryme” (assonance of the typical English nursery rhyme for children “Nursery Rhyme”).

It basically tells a ghost story in a decadent and Victorian setting, but it also touches many of the diffractions and asymmetries that time induces in the artistic inspiration, combining the themes of death and those of reincarnation and sensual love ..

While an 8 year old boy (Henry Hamilton-Smythe) is playing croquet with his girlfriend (Cynthia Jane De Blaise-William, 9 years old), the latter “beheads him” gracefully “with his club.

.But Henry comes back soon … A few days after the fact, Cynthia enters Henry’s room and finds the music box (Musical Box) of the child, then opens it and while the rhyme notes flow “Old King Cole”, Henry’s spirit materializes in front of the little murderer.

But – as Dracula well knew, so much so that he had to become a vampire in order not to suffer the effect – the Oceans of Time cannot be crossed without consequences… – so Henry’s spirit begins to get old quickly and, in short, in front of Cynthia a filthy old man appears demanding sexual satisfaction from the girl, to compensate for the damage caused.

Now, the song suddenly assumes a vertical trend, increasingly pressing, the sounds previous classics cross and overlap with the roaring of distorted notes of guitar and rhythmic in crescendo, above which the voice of Peter Gabriel flies, hoarse and obsessive, screaming several times: “Why don’t you touch me ?? !! ??”, which would be Henry’s injunction-plea to Cynthia. But just then, Henry’s “nurse” enters the room, sees the ghost and throws it on the music box, destroying both.

The music, after the hysterical crescendo, calms down in a classic conclusion, with guitars playing the traditional role of wind instruments.

And then, the ocean of time is recomposed, its waves begin to flow lightly, the images, the notes,words close in other present, past and future eras. Only poetry remains.

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

lascia una risposta