Il romanzo che me lo ha fatto amare definitivamente si chiama “Una solitudine molto rumorosa”, che comincia con una frase magica : “da 35 anni lavoro alla carta vecchia ed è la mia love story.” Poi spiega che da 35 anni per l’appunto pressa carta vecchia e libri, si imbratta con i caratteri, e alla fine assomiglia alle enciclopedie : “sono una brocca di acqua viva e morta, basa inclinarsi un poco e da me scorrono pensieri tutti belli, contro la mia volontà sono istruito.”…

English versionHanta, saggio della non-conoscenza, ammette che spesso non sa se i suoi pensieri sono veramente suoi o vengono da qualcosa che non ha nemmeno letto. Per lavoro deve occuparsi delle distruzione dei libri, perché imballatore di carta da macero ottenuta dai libri censurati dal regime comunista, ma alla fine li riammette in una esistenza concreta sotto forma di flusso ininterrotto di parole e concetti che libera nell’aria e che dal sotterraneo dove passa le giornate mutano forma come in un sortilegio salvifico, diventando sculture geometriche.

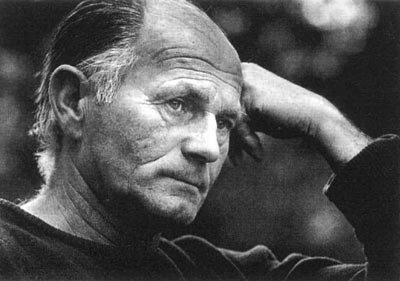

Bohumil Hrabal era nato a Brno nel 1914, ma si trasferì presto a Nymburk e poi a Praga. Nel 1939 i suoi studi di legge furono bloccati dall’invasione della Cecoslovacchia da parte della Germania nazista e lui, per mantenersi, cominciò l’incredibile serie di mestieri che diventerà una cifra di tutta la sua vita.

Una specie di destino a cicli, perché tutto si ripeterà tre volte, con l’avvento del regime comunista e, alla fine, anche dopo la primavera di Praga. Dire che era un personaggio senza schemi è molto riduttivo.

Era un grande bevitore di birra e frequentatore di locali storici (il mio primo giro obbligato per le birrerie di Praga mi ha portato inesorabilmente alla “Tigre d’Oro”, dove passava molto del suo tempo e dove, ora che è morto, i muri sono pieni di sue fotografie (una anche con Clinton..). Era – come lui stesso si è definito – “irresistibilmente attratto dalle sbronze e dal comunismo”.

Con il genere di formazione obbligata, ricevuta attraverso i mille mestieri umili esercitati per sopravvivere, ogni traccia di snobismo era stata del tutto rimossa dal suo mondo immaginario, dove la poesia arretrava per favorire la crescita di un linguaggio diretto, narrativo, quasi da cantastorie, ironico, paradossale, molto tendente al surreale e al grottesco, ma in realtà molto meno popolare di quanto possa sembrare.

Dopo il 1968 il regime operò la censura totale delle sue opere che circolavano solo tramite canali clandestini. La diffusione era però tale da renderlo un maestro riconosciuto, con una crescente fama anche fuori dai confini della Cecoslovacchia.

Non è un eroe, Hrabal, è un essere umano fragile e impaurito che affida la sua consistenza vitale alla letteratura, allo scrivere, e si rifugia nelle sbornie e nella vita da osteria come in cerca di una pausa. E’ proprio in quella terra di mezzo che trova la chiave per interpretare la realtà, lo humour che lo sostiene, le memorie che gli permettono di gestire le paure infinite, di attraversare il tempo del pianto e il Tempo (non meno difficile) della fine del pianto.

In un librino scritto nel 1990 racconta: “ Una domenica, quando ero ancora nella pancia della mia mamma, quell’iracondo di mio nonno prima di pranzo ha trascinato la mia mamma con me dentro il pancino fuori in cortile, ha tirato giù il fucile e ha urlato… In ginocchio che ti sparo! E mia mamma, una ragazzina cresciutella, ha giunto le mani e si è messa a pregare per me… Alla fine è uscita la nonna e ha detto : Venite a mangiare sennò si raffredda!”

Morì il 3 febbraio 1997, durante un ricovero per una lieve malattia in un ospedale di Praga, cadendo da una finestra al quinto piano.

Quasi ogni punto di Praga, almeno di quella storica, celeberrima e quindi inevitabilmente terminale di gite, è ormai letteralmente ricoperto ad ogni ora da folle di turisti, bancarelle di venditori di souvenir, comitive, classi scolastiche, non restano a volte nemmeno gli angoli più elementari per poter scorgere dal Ponte Carlo, il Castello e capirne la grande incombenza sulla città.

Ma una mattina, sarà stato novembre, proprio al risveglio dopo una serata trascorsa in Birreria, mi accorsi di essere stato colpito da una totale, rapidissima e devastante afonia, che si risolse in poche ore ma che, ovviamente, mi impedì di svolgere l’intervento che mi competeva quel giorno (alle 9) in un seminario internazionale in un grande albergo.

Era molto presto, a parte la voce non mi sentivo affatto male e mi venne l’idea di sfruttare l’occasione : presi la metropolitana e mi fiondai all’inizio del Ponte Carlo, riuscendo così a godermelo per almeno un’ora in pressochè totale assenza di gente e di rumori.

Feci tantissime foto, tutta la situazione sembrava quasi irreale, non riuscivo a non pensare che forse vedevo uno dei luoghi simboli di Praga come tante volte l’avranno visto Hrabal, ma anche Kafka, Kundera, e chissà quanti altri.

Poi, con grande rapidità la gente cominciò ad arrivare, le bancarelle vennero riallestite , il vociare e lo schiamazzo generale ripresero potere sul luogo annullandone la magia. Me ne tornai all’albergo, mi sdraiai sul letto per riposarmi e ad attendere che la voce mi tornasse. Ma mi ronzava per la testa una frase, pronunciata una volta da un grande fotografo:

“Non ci sono molte persone nelle mie fotografie, in particolare nei paesaggi. E c’è un motivo, capisci: mi ci vuole del tempo per preparare tutto. Qualche volta la gente c’è anche, ma prima che io sia pronto se ne sono andati. E allora cosa posso fare, non voglio certo costringerli a tornare”.

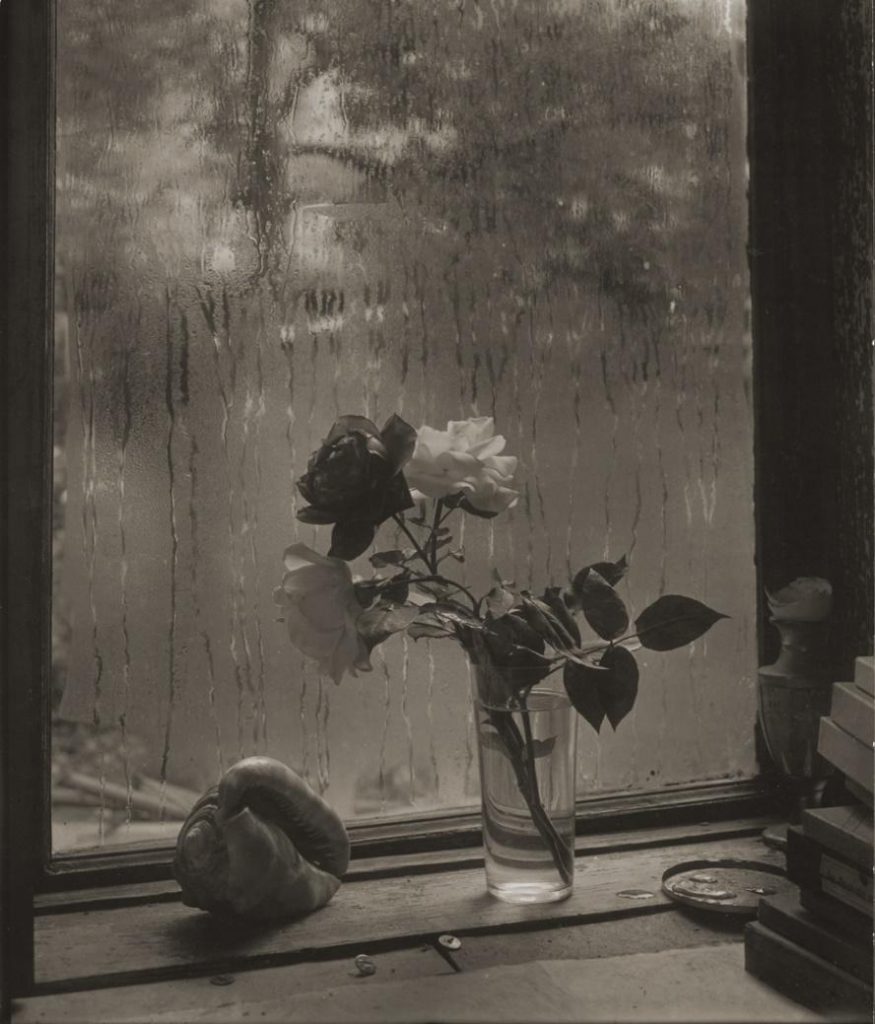

Josef Sudek, nato nel 1896, fu soprannominato il “Poeta di Praga”. Si interessava di fotografia già da prima della guerra ma poi fu arruolato, nel 1915, nell’esercito austro-ungarico, e assegnato al fronte italiano, dove perse il braccio destro.

Resta tre anni nell’ospedale militare e approfondisce le sue competenze fotografiche per poi stabilirsi a Praga, ospitato dall’istituto per gli invalidi di guerra dove resterà fino al 1928. Nel 1920 diviene membro del Circolo dei fotografi dilettanti e nel 1922 si iscrive alla Scuola di Arti Grafiche di Praga studiando con il prof. Karel Novak e iniziando a fotografare professionalmente.

Soggetti di questo primo periodo sono i suoi ex compagni di degenza in ospedale. Non c’è molto altro da dire sulla sua vita, la sua intera biografia è molto scarna, pur essendo molto attivo socialmente e culturalmente (e noto anche per il carattere non facile…) e pur avendo ottenuto attenzione ed encomi per le sue attività e per i suoi molti libri.

I suo veri interessi sono due: Praga, che ama riprendere evidenziandone panoramicamente le architetture antiche e moderne nella loro complessità, soprattutto dagli anni ’50, quando acquista una fotocamera Kodak Panorama del 1894, la cui lente a molla produce un negativo di 10 cm x 30 cm, e la Bellezza…

Sudek scatta continuamente foto agli oggetti quotidiani, alla sua casa, a quanto vede (seguendo le stagioni) dalla sua finestra, al suo giardino, alle nature morte, e alla sembianza che le cose, in certe angolature e in certe variazioni della luce, assumono quasi trasformandosi in elementi irreali in un’atmosfera lirica. Una ricerca di realismo romantico che durerà tutta la vita.

Morì all’età di 80 anni dopo aver curato la sua ultima mostra al Museo di Arti decorative a Praga.

Il suo è stato un viaggio infinito, continuo, compiuto per lo più senza muoversi da casa, e mi ha sempre fatto interrogare sui tanti sensi del Viaggio.

Si viaggia in nome della conoscenza, per desiderio di conoscenza, senz’altro, ma andando avanti negli anni si comincia a intuire che il desiderio, in fondo, è quello di incontrarsi, di incontrare l’altro, il diverso e uguale che batte chissà quali porti. La Veronica di Kieslowski, il doppio di Borges e Cortàzar. Senza effettiva fisicità, credo. Senza alternativa vivente, probabilmente. Però mi piace. E forse spiega tante cose, tante paure, del buio e nel buio.

E forse spiega questo senso di smarrimento che provo nel guardare la gente che sciama fuori dagli uffici, nell’aria percorsa da un accenno di nebbia, al tramonto, e si avvia per i mille vicoli della città vecchia, schivando le bancarelle di cianfrusaglie e i miracoli che non ci sono più, forse perché non richiesti.

Io giro in tondo per questo labirinto dove Est e Ovest sono convenzioni, come le religioni e le fedi politiche, cercando l’uomo calmo e dolce che avrei sempre voluto essere.

L’altro forse, starà cercando il nevrotico presuntuoso e scontento che scrive in questo momento.

Il rimpianto. La malattia dentro, che frigge e raggela.

Il rimpianto per qualcosa che neanche conosciamo.

E con gli altri, il nascondino dei sentimenti.

A ben guardare il mondo è una figura grottesca, bifronte.

I poeti dovrebbero comunicare, in tutti i modi, a tutti i costi la sensazione che si prova nella Casa Comune, rimasta vuota.

Tutto. Perfino questa mitologia europea della Grande Sofferenza. Ci sono, apparentemente, più modi di partire.

Qualcuno fuggiva dall’Est.

Si diceva : “E’ andato via…” – sussurrando.

Ritrovarsi dall’altra parte. La sensazione del fuggitivo, l’appartenenza ad un’idea piuttosto che ad un luogo geografico.

Dove i bisogni si scontrano con la proprietà neutra delle cose, dove non si può recitare.

Nelle partenze conta il pensiero del ritorno, oppure il riconoscersi tanto lontani da divenire in se stessi un’idea.

Deve essere come sentirsi sempre ubriachi, vedere le luci tremolare.. il letto ondeggiare..sentirsi sempre come appena usciti di casa, senza i vestiti più comodi, senza una foto di padre o madre, senza storie di famiglia nel cassetto, con la paura di non conoscere più il contenuto dei cassetti…

Sono sempre poche ore, dopo.

Le cose non si presentano mai in maniera semplice, e forse non sono mai veramente semplici e chiare, fino in fondo. Dopo tutto.

Nell’incredibile miscuglio di razze e nazionalità, al capolinea dei pullman della Periferia Nord, in mezzo ai Ceki, ai Polacchi, agli zingari, c’era un tipo vestito da Cow Boy – folcloristico, ma con tanto di verissima pistola al fianco.

A very noisy solitude

The novel that made me love him definitively is called “A very noisy solitude”, which begins with a magic phrase: “for 35 years I have been working on old paper and it is my love story.” Then he explains that for 35 years, he pressed old paper and books, he smeared with characters, and in the end he looks like encyclopedias: “I am a jug of living and dead water, it is enough to lean a little and from me all thoughts flow , against my will I am educated. ”… Hanta, a wise man of non-knowledge, admits that he often does not know if his thoughts are truly his or come from something he has not even read. For work he must deal with the destruction of books, because a waste paper packer obtained from books censored by the communist regime, but in the end he readmits them into a concrete existence in the form of an uninterrupted flow of words and concepts that he frees in the air and that from the underground where he spends the days they change shape as in a saving spell, becoming geometric sculptures,

Bohumil Hrabal was born in Brno in 1914, but soon moved to Nymburk and then to Prague. In 1939 his law studies were blocked by the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany and he, to maintain himself, began the incredible series of professions that will become a figure of his whole life. A sort of fate in cycles, because everything will be repeated three times, with the advent of the communist regime and, in the end, even after the Prague spring. To say that he was a character without patterns is very simplistic. He was a great beer drinker and frequenter of historical places (my first obligatory tour of the Prague breweries led me inexorably to the “Golden Tiger”, where he spent much of his time and where, now that he is dead, the walls are full of his photographs…one also with Clinton ..) He was – as he defined himself – “irresistibly attracted to drunkenness and communism”.

With the kind of compulsory training, received through the thousand humble professions exercised to survive, every trace of snobbery had been completely removed from its imaginary world, where poetry receded to encourage the growth of a direct, narrative language, almost like a storyteller, ironic, paradoxical, very tending to surreal and grotesque, but in reality much less popular than it might seem. After 1968 the regime made the total censorship of his works that circulated only through clandestine channels. The diffusion, however, was such as to make him a recognized master, with a growing fame even outside the borders of Czechoslovakia.

Hrabal is not a hero, he is a fragile and frightened human being who entrusts his vital consistency to literature, writing, and takes refuge in the hangover and in the life of a tavern as if looking for a break. It is precisely in that middle ground that he finds the key to interpreting reality, the humor that sustains him, the memories that allow him to manage infinite fears, to cross the time of crying and the time (no less difficult) of the end of crying.

In a booklet written in 1990 he says: “One Sunday, when I was still in my mom’s tummy, that angry grandfather before lunch dragged my mom with me inside the tummy out into the courtyard, pulled down the rifle and he screamed … On my knees I’ll shoot you! And my mom, a grown-up girl, put her hands together and started praying for me .. At the end my grandmother came out and said: Come and eat or else it will cool down! ”

He died on February 3, 1997, during a hospitalization for a mild illness in a Prague hospital, falling from a window on the fifth floor.

Almost every point of Prague, at least of the historical one, famous and therefore inevitably the terminal of trips, is now literally covered at every hour by crowds of tourists, stalls of souvenir vendors, groups, school classes, sometimes even the most hidden corners are not left to be able to see the Castle from the Charles Bridge and understand its great impact on the city.

But one morning, it must have been November, just after waking up after an evening spent in a Brewery, I realized that I had been struck by a total, very rapid and devastating aphonia, which resolved in a few hours but which, obviously, prevented me from carrying out the intervention that was up to me that day (at 9) in an international seminar in a large hotel.

It was very early, apart from the voice I did not feel bad at all and I had the idea of taking advantage of the opportunity: I took the subway and I slingshot at the beginning of the Charles Bridge, thus managing to enjoy it for at least an hour in almost total absence of people and noises.

I took lots of photos, the whole situation seemed almost unreal, I couldn’t help thinking that maybe I saw one of the symbolic places in Prague as Hrabal will have seen it many times, but also Kafka, Kundera, and who knows how many others.

Then, with great rapidity, people began to arrive, the stalls were rearranged, the shouting and the general shouting regained power over the place, canceling out the magic. I went back to the hotel, lay down on the bed to rest and wait for the voice to come back to me. But a phrase buzzed through my head, once uttered by a great photographer:

“There aren’t many people in my photographs, particularly in the landscapes. And there is a reason, you understand: it takes me some time to prepare everything. Sometimes people are there too, but before I am ready, they leave they are gone. So what can I do, I certainly don’t want to force them to come back “.

Josef Sudek, born in 1896, was nicknamed the “Prague Poet”. He had been interested in photography since before the war but was then drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army in 1915 and assigned to the Italian front, where he lost his right arm. He spent three years in the military hospital and deepened his photographic skills and then settled in Prague, hosted by the Institute for the War Disabled where he remained until 1928. In 1920 he became a member of the Circle of amateur photographers and in 1922 he enrolled in the School of Graphic Arts in Prague studying with prof. Karel Novak and starting to photograph professionally. Subjects of this early period are his former hospital companions. There is not much more to say about his life, his entire biography is very sparse, despite being very socially and culturally active (and also known for his not easy character …) and despite having obtained attention and commendations for his activities and for his many books. His real interests are two: Prague, which he loves to shoot by highlighting its ancient and modern architectures in their complexity, especially from the 1950s, when he purchased a Kodak Panorama camera from 1894, whose spring lens produces a negative of 10 cm x 30 cm, and Beauty …Sudek continuously takes photos of everyday objects, his home, what he sees (following the seasons) from his window, his garden, still lifes, and to the semblance that things, in certain angles and in certain variations of light, take on almost transforming themselves into unreal elements in a lyrical atmosphere. A search for romantic realism that will last a lifetime.

He died at the age of 80 after curating his latest exhibition at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

His was an infinite, continuous journey, made mostly without moving from home, and he always made me wonder about the many senses of the Journey. We travel in the name of knowledge, out of desire for knowledge, of course, but going forward over the years we begin to understand that the desire, after all, is to meet, to meet the other, the different and equal that beats who knows which ports. Kieslowski’s Veronica, twice as many as Borges and Cortàzar. Without actual physicality, I think. Without a living alternative, probably. But I like it. And perhaps it explains many things, many fears of the darkness.

And perhaps it explains this sense of bewilderment that I feel in watching the people swarming out of the offices, in the air crossed by a hint of fog, at sunset, and walking through the thousand alleys of the old city, dodging the stalls of junk and miracles that are gone, perhaps because they are not required.

I go round and round this labyrinth where East and West are conventions, such as religions and political faiths, looking for the calm and sweet man I always wanted to be.

The Other perhaps, is looking at the presumptuous and discontented neurotic who is writing at the moment.

Regret. The disease inside, which fry and freeze.

Regret for something we don’t even know.

And with others, the hide and seek of feelings.

On closer inspection, the world is a grotesque, two-faced figure.

Poets should communicate, in all ways, at all costs, the feeling that is felt in the Common House, which has remained empty.

All. Even this European mythology of the Great Suffering. There are apparently more ways to go.

Someone was fleeing from the East.

It was said: “He went away …” – whispering.

Find yourself on the other side. The fugitive’s feeling, belonging to an idea rather than a geographical place.

Where needs collide with the neutral property of things, where one cannot act.

In departures, the thought of the return counts, or the recognition of oneself so far away as to become an idea in oneself.

It must be like always feeling drunk, seeing the lights flicker .. the bed swaying .. always feeling like you have just left the house, without the most comfortable clothes, without a photo of father or mother, without family stories in the drawer, with fear to no longer know the contents of the drawers …

It’s always a few hours later.

Things never present themselves in a simple way, and perhaps they are never really simple and clear, to the end. After all.

In the incredible mix of races and nationalities, at the terminus of the coaches of the Northern Suburbs, in the midst of the Ceki, the Poles, the gypsies, there was a guy dressed as a Cow Boy – folkloric, but with a very real gun at his side.

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

lascia una risposta