“I have nothing to say and I’m saying it. And that is poetry as I needed it”

(John Cage)

Il fotografo giapponese Masao Yamamoto (Gamagori City nella prefettura di Aichi, Giappone, 1957), fortemente ispirato dalla filosofia Zen, ha creato uno stile orientato alla ricerca spirituale dell’idea di bellezza.

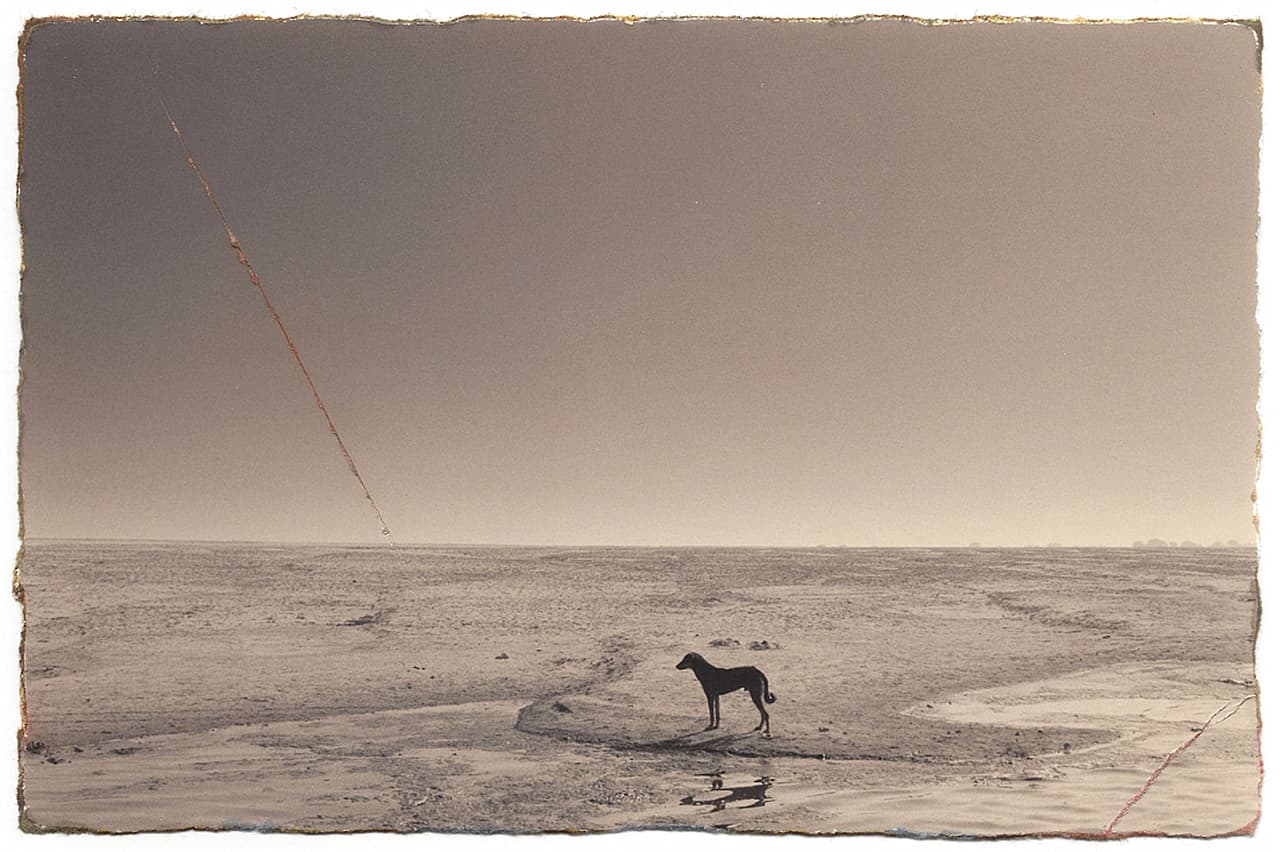

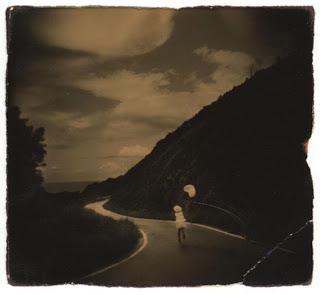

Ancora negli anni ’80 iniziò una serie di lavori di piccolo formato, intitolata Box of Ku, che fossero leggibili come degli Haikus, per incoraggiare l’osservatore ad estrarre i propri ricordi e le proprie suggestioni davanti a piccoli e semplici oggetti catalizzatori di memoria.

English versionQueste immagini senza tempo sono infatti considerate da Yamamoto essenzialmente come elementi materiali, oggetti da toccare, manipolare e ridefinire.

“Mi piace l’idea che le mie immagini possano sembrare quelle di un anonimo fotografo di chissà dove e chissà quando, trovate per caso in qualche mercatino delle pulci, dotate di fascino e mistero tanto da permettere a ciascuno di scoprirle e inventarci sopra altre storie, le proprie storie…”

In una delle sue serie più recenti (Kawa=Flow) Yamamoto usa la metafora del fiume per dedicarsi, insieme all’osservatore, ad una specie di processo meditativo.

Una riflessione sulla natura e sull’interiorità attraverso l’uso di immagini evanescenti e delicate in bianco e nero oppure virate in tonalità beige, nel dichiarato tentativo di “rivelare l’ordinario come qualcosa di straordinario”.

Del lavoro di Masao Yamamoto (molto popolare in Italia), mi colpisce proprio questo: le sue immagini non hanno nulla da dire, non vogliono significare nulla, ti trasportano in una sorta di vuoto tangibile, in un dialogo con tempi e riflessi fuori dal tempo stesso.

Ma soprattutto queste foto esistono nel silenzio, nel silenzio che impongono alla mente, lo stato necessario per entrare in un diverso principio di osservazione (dove, dall’altra parte dell’immagine, non ci sei altro che te che osservi) e di ascolto, di suoni e movimenti, di rumori e fruscii che l’esterno-interno del mondo regala, e che sta a noi trasformare in musica.

John Cage, nato a Los Angeles nel 1912 e morto nel 1992 a New York, è stato il compositore sperimentale americano più influente (e più discutibile) del ventesimo secolo. È stato considerato (ma lui non ha mai detto di esserlo) il padre dell’indeterminismo.

Un artista ispirato dallo Zen che ha espulso tutte le nozioni della scelta dal processo creativo. Rifiutando la conseguenza logica in quanto principio di composizione

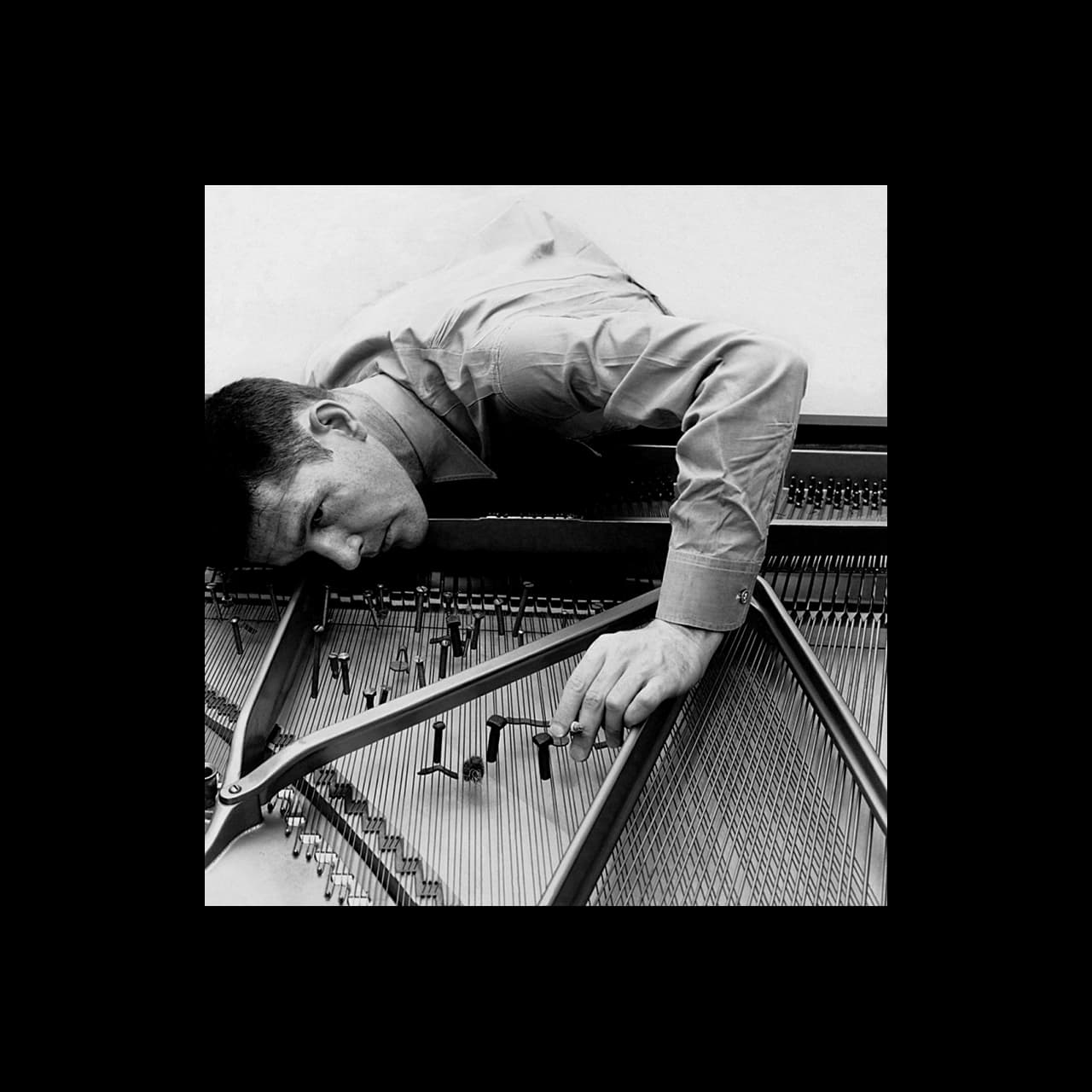

Cage ha elaborato un linguaggio personale e rivoluzionario partendo dalla dissacrazione totale delle regole musicali classiche e tradizionali. Una sua invenzione sono le composizioni per “pianoforte preparato”.

Scartava la costruzione musicale basata sulla struttura armonica in favore di una struttura ritmica, intesa semplicemente come successione di durate, che potevano ospitare qualsiasi suono.

L’opera musicale di John Cage ha suscitato una di quelle reazioni tipiche nella nostra cultura: tutti ne hanno parlato ma quasi nessuno l’ha ascoltata.

Io, come molti, ho sempre pensato che il lavoro musicale di Cage – che pure conosco e, con qualche difficoltà, apprezzo – non sia prescindibile dalla sua essenza, dalla sua presenza nel mondo in quanto interprete del mondo stesso, più un filosofo che un musicista, anzi: un musicista che voleva seguire il principio Zen di assoluto/vuoto, e che, quindi, si rivolgeva alla musica come manifestazione del vuoto e della natura in senso più lato.

John Cage è stato autore di libri secondo me bellissimi.

In uno di questi, Per gli Uccelli, che è a metà tra la autobiografia e la teoria musicale applicata alla filosofia zen, è contenuta l’affermazione che più mi ha colpito e che più me lo ha fatto amare (vado a braccio): non c’è nessun bisogno di comporre, di scrivere della musica, la musica c’è già, la musica è nell’aria, è nella natura e nei suoni e nei rumori che ci circondano… scrivere musica vuol dire catturare questi suoni, o anche per difetto, catturare il silenzio, che vale allo stesso modo.

Penso a lavori quali Imaginary landscape e First construction (in metal) del 1939, in cui ogni regola tecnica viene oltrepassata per lasciare spazio ad un’espressione che trasforma ogni suono casuale in musica e dove la forma e l’interpretazione vengono lasciate alla libertà dell’interprete, tanto che in molte composizioni l’autore si limita solamente a prescrivere all’esecutore diversi comportamenti legati ad stati d’animo, senza preoccupazioni per i risultati sonori.

La partitura 4.33, che può essere utilizzata come manifesto complessivo dell’estetica e della filosofia di Cage, è in realtà un momento bianco, privo di musica, ove – per la durata di tempo che dà il titolo al brano – la musica viene creata dai rumori della sala da concerto, bisbigli, colpi di tosse, scricchiolii vari, ed anche da quelli che provengono dall’esterno.

Cage ha dimostrato così che il silenzio assoluto non esiste (nemmeno in una stanza totalmente insonorizzata, perché anche lì uno sente almeno il proprio battito cardiaco). Il silenzio sarebbe da intendersi dunque semplicemente come un rumore di sottofondo.

Durante il primo movimento di questa leggendaria prima esecuzione del brano (n.d.R.: 29 agosto 1952, Maverick Concert Hall, vicino Woodstock, New York, ad opera del pianista David Tudor), si sentiva il vento che spirava, nel secondo la pioggia, e nel terzo il pubblico che parlottava o si alzava indignato per andarsene.

Diceva Cage stesso:

“Sentivo e speravo di poter condurre altre persone alla consapevolezza che i suoni dell’ambiente in cui vivono rappresentano una musica molto più interessante rispetto a quella che potrebbero e ascoltare a un concerto “.

Ma ovviamente non è stato così.

Visto di volta in volta come un genio, come un fenomeno da baraccone, come un ciarlatano, o comunque sempre controverso, Cage ha portato avanti la sua grande avventura fino al 1992.

Io ho avuto la fortuna di incontrarlo (due volte: nel 1978 e nel 1989) e non dimenticherò mai la sua espressione serena e sorridente. E’ l’unico personaggio famoso da cui mi sia fatto fare l’autografo, che conservo devotamente sulla sua foto.

L’altro suo folgorante libro, A Year from Monday, contiene, in una forma espositiva e grafica frequentemente affidata al caso, anche numerosissimi brevi aneddoti di sapore decisamente Zen.

E’ uno di quei libri ai quali ritorno sempre nei momenti difficili della mia vita, uno di quei libri dove non è necessario capire, trovare riflessioni, interpretazioni, ricette, ma solamente sentire la musica del tempo, del vuoto e della vita, pensare che, in fondo, noi stessi siamo musica, lo siamo sempre stati e torneremo ad esserlo.

E’ uno di quei libri che mi servono quando corro il rischio di prendermi troppo sul serio… perché quando lo metto giù mi sembra di sentire la sua voce che dice ridendo: “ma va….”

About objects and sounds of silence

“I have nothing to say and I’m saying it. And that is poetry as I needed it ”

– (John Cage)

The Japanese photographer Masao Yamamoto (1957), strongly inspired by Zen philosophy, created a style oriented towards the spiritual search for the idea of beauty.

Since the begin of the 80s he realized a series of small format works, entitled “Box of Ku”, which were legible as Haikus, to encourage the observer to extract their memories and suggestions in front of small and simple objects catalysing memory .

These timeless images are in fact considered by Yamamoto essentially as material elements, objects to be touched, manipulated and redefined.

“I like the idea that my images may look like those of an anonymous photographer of who knows where and who knows when, found by chance in some flea market, with charm and mystery so as to allow everyone to discover them and invent other stories over them , their own stories … “

In one of his most recent series (Kawa = Flow) Yamamoto uses the metaphor of the river to devote himself, together with the observer, to a kind of meditative process.

A reflection on nature and interiority through the use of evanescent and delicate black and white images or veering in beige shades, in the declared attempt to “reveal the ordinary as something extraordinary”.

This is what strikes me about Masao Yamamoto’s work (very popular in Italy): his images have “nothing” to say, they don’t want to “mean” anything, they transport you in a sort of tangible void, in a dialogue with the times and reflections out of time itself.

But above all these photos exist in the silence, in the silence that they impose on the mind, the state necessary to enter a different principle of observation (where – on the other side of the image there is nothing but you that observe) and listening, of sounds and movements, of noises and rustles that the outside-inside of the world gives, and that it’s up to us to transform into music.

John Cage, born in Los Angeles in 1912 and died in 1992 in New York, was the most influential (and most controversial) American experimental composer of the twentieth century. He was considered (but he never said he was) the father of indeterminism.

Another artist definitely inspired by Zen who has expelled all the notions of choice from the creative process. Rejecting the logical consequence as a principle of composition

Cage developed a personal and revolutionary language starting from the total desecration of classical and traditional musical “rules”. One of his inventions are the compositions for “prepared piano”.

He discarded the musical construction based on the harmonic structure in favor of a rhythmic structure, intended simply as a succession of durations, which could accommodate any sound.

John Cage’s musical work has sparked one of those typical reactions in our culture: everyone talked about it but almost nobody listened to it.

I always thought that Cage’s musical work – which with some difficulty, I appreciate – is not separable from its “essence”, from its presence in the world as an interpreter of the world itself, plus a philosopher that a musician, indeed: a musician who wanted to follow the Zen principle of absolute / emptiness, and who therefore turned to music as a manifestation of emptiness and nature in the broadest sense.

John Cage was also the author of books that I think are beautiful.

In one of these, “For the Birds”, which is halfway between autobiography and the musical theory applied to eastern philosophy, the statement that struck me most and that made me love him most is contained: there is no no need to compose, to write music, the music is already there, the music is in the air, it is in nature and in the sounds and noises that surround us … writing music means capturing these sounds, or even by default, capture the silence, which is equally true.

I think of works such as “Imaginary landscape” and “First construction (in metal)” of 1939, in which every technical rule is exceeded to leave room for an expression that transforms every random sound into music and where form and interpretation are leave to the freedom of the interpreter, so much so that in many “compositions” the author limits himself only to prescribing various mood-related behaviors to the performer, without concern for the sound results.

The score “4.33”, which can be used as an overall manifesto of Cage’s aesthetics and philosophy, is actually a white moment, devoid of music, where – for the duration of time that gives the title to the piece – the music is created by the noises of the concert hall, whispers, coughs, various crunches, and also by those coming from outside.

Cage has thus demonstrated that absolute silence does not exist (not even in a totally soundproofed room, because even there one at least hears his heart beat). The silence would therefore be understood simply as a background noise.

During the first movement of this legendary first “performance” of the song, the wind blew, in the second the rain, and in the third the audience who talked or stood up indignantly to leave. .- “I felt and hoped – said Cage – to be able to lead other people to the awareness that the sounds of the environment in which they live represent a much more interesting music than they could and listen to at a concert”.

But obviously it was not so.

Seen from time to time as a genius, as a freak phenomenon, as a charlatan, or in any case always controversial, Cage continued his great adventure until 1992.

I was lucky enough to meet him (twice: in 1978 and 1989) and I will never forget his serene and smiling expression.

He is the only famous person from whom I was autographed, which I devoutly keep on his photo.

His other dazzling book, “A Year from Monday”, contains, in an exhibition and graphic form frequently entrusted to chance, also numerous short anecdotes with a decidedly Zen flavor.

It is one of those books to which I always return in the difficult moments of my life, one of those books where it is not necessary to understand, find reflections, interpretations, recipes, but only to hear the music of time, emptiness and life, to think that after all, we ourselves are music, we always have been and we will return to it.

It is one of those books that I need when I run the risk of taking myself too seriously … because when I put it down I seem to hear his voice saying laughing: “come on…let it all go”

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

Articolo che mi è piaciuto molto, ringrazio l’ autore perché tratta un tema che mi è caro: Cage e altri musicisti che nei 60 fecero discendere la composizione musicale dallo Zen (di recente ho appreso che il carattere che in cinese antico indica la musica, significa “piacere, felicità” ed anche “medicina”… da qui si potrebbero trarre molte riflessioni).

In un certo senso, questo tipo di musica rappresenta il trionfo della spontaneità opposta alla tecnica. Ma non solo, richiama insegnamenti dalla Quarta Via (il suono sospeso sull’abisso…) e poi quelli del senso e significato della musica stessa.

In un mio articolo di prossima uscita, ho ascritto un profumo ad un’immagine. Sebbene il tema trattato appaia niente affatto filosofico, credo che nell’upgrade percettivo i comparti stagni non ci appartengano più. Ne è esempio il rock, in cui troviamo un periodo realista che insegue il senso figurativo (nel rock sinfonico).

Tornando a Cage, non credo si possa distinguere tra musica e filosofia.

Mettendo il grandangolo direi che la musica è parte intrinseca del mondo, occorre apprendere una nuova dimensione nella creazione e nell’ascolto della musica, non necessariamente polifonica o melodica. Il vuoto di Cage ci insegna che il suono non termina nel silenzio. Occorre oltrepassare la scala Wittgensteiniana (lui sosteneva che servisse una scala per raggiungere il silenzio, ma la trappola è quella di continuare a servirsene una volta raggiunto l’obiettivo). E Schönberg, con i dodici suoni, si ritrovò in un vicolo cieco, proprio nel tentativo di infrangere il sistema tonale.

Credo che il problema possa essere costituito dalla predilezione occidentale della metafisica del senso.

Forse la musica non deve esprimere niente, non deve essere realistica, mentre siamo abituati a dover esprimere qualcosa entro certe linee prestabilite. Accade nella musica, ma anche nella scrittura (meno nella pittura). Ma se questo è vero quando mi trovo a commentare l’opera di terzi, nel momento in cui l’ artista esprime sé stesso, dovrebbe essere libero da catene (in proposito mi sovviene la prosa spontanea di Kerouac). Di contro, il prosatore o il compositore polifonico non sa improvvisare: una pausa, cambiamento, lo turba e vuole riempirlo.

Certo, l’improvvisazione non è il fine della musica, piuttosto la ricerca di un nuovo linguaggio, potrebbe somigliare ad una bozza o ad una prova musicale che non si presta ad essere riascoltata. Pena la perdita di qualcosa. Su questo mi piacerebbe conoscere il parere dell’autore dell’articolo.

Non mi sento, tuttavia, di allinearmi a coloro che in tale contesto ascrivono demeriti a Bach o Mozart, dico solo che imparare a considerare tutto il suono del mondo, sia un modo per allargare la mente. Anche se si tratta di tornare alla monodia o ad ascoltare il suono del silenzio o quello del “battere di una sola mano”…

Nell’entusiasmo per l’articolo, ho scritto un’imprecisione, che rettifico: il carattere cinese che indica “medicina” non è il medesimo di “musica”, ma è molto simile ad esso. Rileggendo il suo articolo, aggiungerei un’altra considerazione, ovvero che Monet non si diede pena di trasgredire quando dipinse Impressione, sole nascente. Miles Davis non si curò degli schemi del jazz…

Forse è vero che, per liberare l’arte, bisogna avere il coraggio di non censurarsi.

Grazie ancora per questo interessante contributo che non cessa di ispirare.

Solo per ringraziare Jo Gabel per i commenti, molto interessanti.