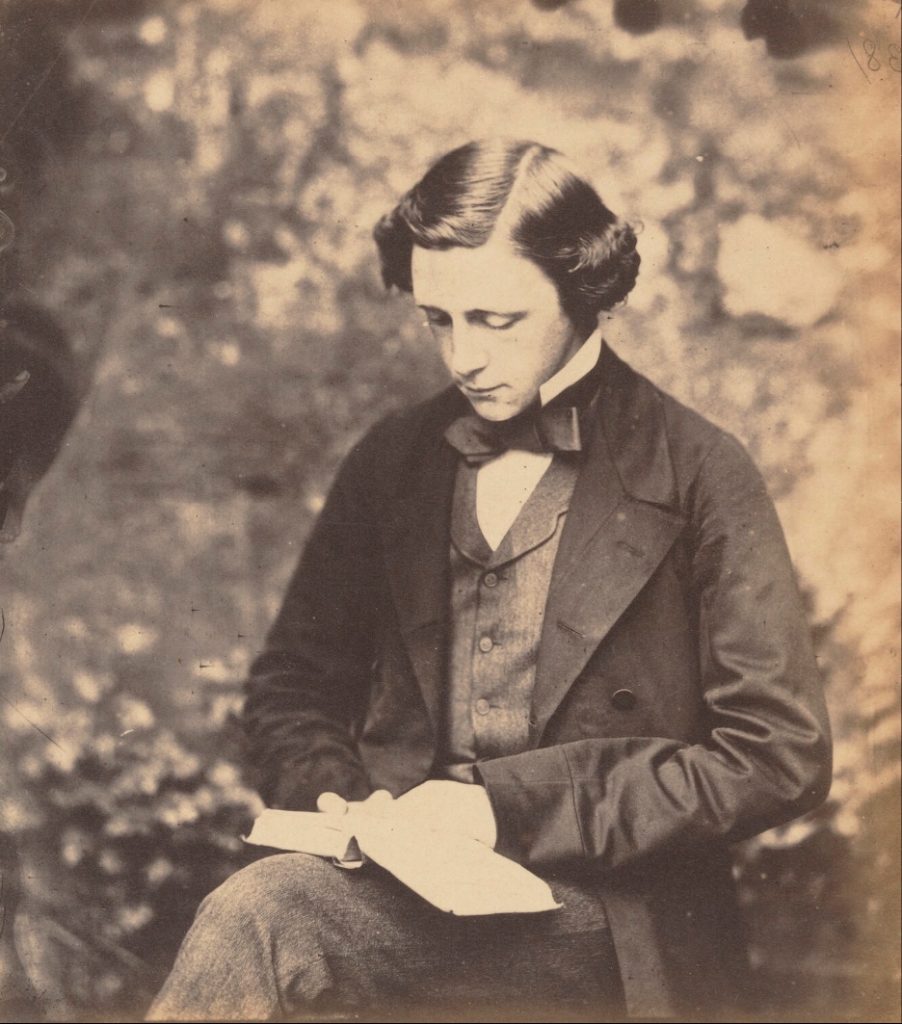

Charles Dodgson (1832-1878), è stato un reverendo, scrittore, matematico, fotografo e logico britannico. Ma tutto il mondo lo conosce con il suo pseudonimo: Lewis Carroll. E lo conosce soprattutto perché ha scritto niente di meno che Le avventure di Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie, pubblicato per la prima volta nel 1865, e seguito da Attraverso lo specchio (1872).

English versionQuesti due romanzi, generalmente considerati come un unicum, lungi dall’essere confinati nella narrativa per ragazzi, hanno incontrato un tale favore popolare e l’entusiasmo di una tale varietà di lettori di ogni età, spessore, cultura, nazionalità e professione, da essere comunemente considerati tra le opere letterarie più celebri di ogni tempo.

Nel Paese delle Meraviglie – dove Alice sconfina casualmente, sognando di inseguire un coniglio bianco – tutte le regole logiche, linguistiche, fisiche e matematiche sono in qualche modo parallele a quelle del mondo reale, risultandone inevitabilmente invertite e concretamente rovesciate. Perché la piccola Alice intraprende questo viaggio? Semplicemente perché desidera un altro punto di vista, una realtà e un paesaggio fisico e umano dove tutto è rovesciato, un mondo allo specchio..

Il romanzo, che contiene numerose chiavi di lettura, è comunemente visto come una metafora del processo di crescita.

Il Paese delle meraviglie permette ad Alice di scuotersi dallo stato di immobilità indotto dalla severa e noiosa educazione vittoriana, stimola la sua curiosità, la porta a guardarsi attorno, a ragionare con la sua testa, ad accettare che si può anche sbagliare e, comunque, a scoprire una nuova parte di sé, quella che la porterà a rivedere tutte le sue precedenti certezze e a crearne di nuove, grazie anche ai personaggi che incontra (Pinco e Panco, Il Bianconiglio, lo Stregatto, la regina, ecc.). E questo solo per rimanere in una lettura superficiale del racconto.

A me – che nei miei seminari cito molto spesso Alice – piace pensare che forse, imparando un’altra logica, la bambina incontra il corretto funzionamento delle cose, perché il sovvertire le regole le fa intuire come in fondo sia il gioco a dirigere il senso e non il contrario.

Il famoso dialogo con lo Stregatto ne è un esempio :

Alice: Volevo solo chiederle che strada devo prendere!

Stregatto: Beh, tutto dipende da dove vuoi andare…

Alice: Oh, veramente importa poco, purché io riesca a uscire di qui.

Stregatto: E allora importa poco che strada prendi, no?

Ancora una volta metafora esistenziale del fatto che per crescere, la strada da trovare non può essere una qualsiasi ma deve essere la propria.

Ma la storia, tra fantasia e realtà, è ancora più complessa. Lewis Carroll è anche un grande fotografo, un antesignano introdotto all’arte addirittura da Oscar Rejlander, uno dei pionieri della fotografia.

Per lui (che in definitiva è un… uomo “di Dio) la Fotografia si rivela ideale per esprimere ciò che chiamava bellezza: uno stato di grazia, di perfezione morale, estetica e fisica da cercare e trovare nelle arti, certo, ma anche nelle formule matematiche e soprattutto nella figura umana, specialmente se femminile, e specialmente se innocente.

Insomma: oltre la metà delle fotografie di Carroll sono di bambine, le quali (spesso fotografate nude) apponevano successivamente la propria firma in un angolo della stampa. Inutile dire che questa passione (dai risultati esteticamente meravigliosi: le immagini che ci sono giunte sono molto belle) gli creò una fama di “pedofilo”, quando invece il suo obiettivo era quello di liberarsi (e liberare le giovani modelle) dall’oppressivo fardello della simbologia vittoriana, immaginandole più come creature della natura piuttosto che come irreprensibili damigelle.

Ma Carroll fece ritratti anche per personaggi di spicco del suo tempo come John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron e Alfred Tennyson. Ora è considerato uno dei padri della fotografia moderna.

Tornando alle sue giovanissime modelle, sapete come si chiamava la sua preferita? Alice Liddell. Ed è proprio lei (figlia del decano di Christ Church di Oxford e della quale conosciamo perfettamente il volto) che nella fantasia di Carroll finisce nel paese delle meraviglie; è sempre lei che, esattamente sei mesi dopo il viaggio nel Paese delle Meraviglie, sonnecchiando su una poltrona del suo salotto, si chiede cosa ci sia dall’altra parte dello specchio e, con sua grande sorpresa, riesce a passarci attraverso ed a trovare una risposta alle sue curiosità.

Al di là dello specchio Alice incontrerà fiori parlanti, personaggi della scacchiera e stranissimi animali, oltre che tutti i personaggi delle sue filastrocche preferite (quelle tipiche della tradizione inglese) come gli assurdi gemelli Tweedledee e Tweedledum e Humpty Dumpty.

Ma Alice, mentre è occupata ad allargare ulteriormente il suo punto di vista visitando il paesaggio inquietante che è “dall’altra parte” dello specchio, non si accorge che, fermo e rigidamente bloccato, nei paraggi dello specchio stesso (proprio da dove è entrata lei) c’è anche un altro bambino, che forse potrebbe giovarsi molto dell’aiuto di Alice e della sua esperienza nell’altrove…

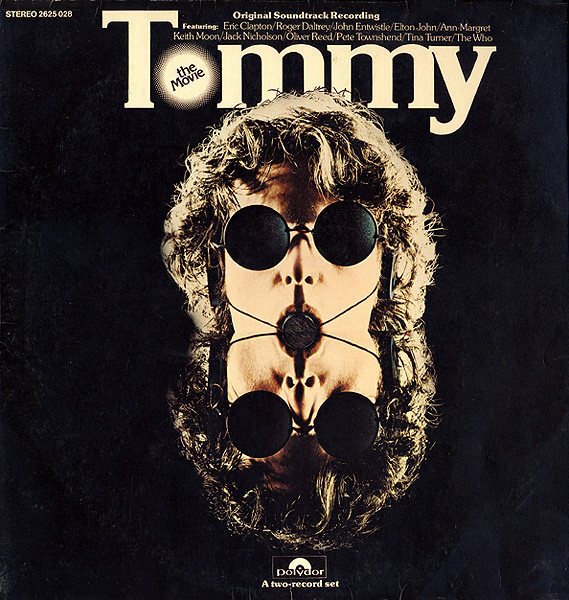

Tommy è un disco degli Who. Uscito nel 1969 è un capolavoro della storia del rock, un’opera dalla quale verrà poi tratto un film (omonimo) di Ken Russell.

Tommy è un ragazzo che assiste (da dietro uno specchio…) all’omicidio dell’amante della madre da parte del padre, aviatore britannico al ritorno dal fronte. I genitori di Tommy, ordinano al bambino di non dire, vedere e sentire nulla (See me, Feel me, Touch me, Heal me… è la canzone che come leitmotiv attraversa l’intera opera e che gli Who eseguiranno pochi mesi dopo al Festival di Woodstock, entrando definitivamente nella leggenda.

Tommy riceve l’ordine traumatico e diviene così muto, cieco e sordo. In pratica, è come se rimanesse “dietro lo specchio”, ma in un ordine sovrapposto e parallelo al reale, dove l’assenza di logica e il ribaltamento del senso comune, che per Alice si popola di buffe e paradossali figure in qualche modo didattiche, per lui diviene un autentico calvario, esposto com’è ad ogni tipo di violenza, abuso e sopraffazione da parte dei normali che lo circondano.

Ma poi avviene il riscatto: Tommy, viaggiando attraverso l’unica magia che può praticare, l’intuito, scopre di essere un fantastico giocatore di flipper.

In breve tempo sbaraglia chiunque altro, anche il più grande, il campione del mondo, che, sbalordito, lo chiama “Pimball Wizard” (mago del flipper) e, rivolgendosi al pubblico (nella canzone) cerca di spiegare cosa prova a vedere questo ragazzo che “gioca d’intuito. E’ cieco, muto e sordo ed è un mago del Flipper. Non ha nulla che lo distrae ma non può vedere le luci, i segnali, i colori, i flash, e non può sentire i campanelli e le vibrazioni della macchina. Lui gioca secondo il senso dell’olfatto, e non sbaglia mai..”

Tommy, una volta ricco e famoso, riuscirà però a riacquistare la normalità, la voce, l’udito, la vista… solo quando la madre distruggerà lo specchio, permettendogli così finalmente di “uscire dall’altra parte” e, magari, di incontrare da quelle parti una graziosa ragazza che, intanto (come lui, del resto), si è fatta proprio grande…

Through the looking-glass: children, photographers, musicians, white rabbits and cheshire cats…

Charles Dodgson (1832-1878) was a British clergyman, writer, mathematician, photographer and logician, but the whole world knows him by his pseudonym: Lewis Carroll. And he’s known above all because he wrote nothing less than “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, published for the first time in 1865, and followed by “Through the looking-glass”.

These two novels, generally considered as a “unicum”, far from being confined to children’s fiction, have met with such popular favor and the enthusiasm of such a variety of readers of all ages, culture, nationality and profession, to be commonly considered among the most famous literary works of all times.

In the “Wonderland” – where Alice accidentally crosses over, dreaming of chasing a white rabbit – all the logical, linguistic, physical and mathematical rules are somehow “parallel” to those of the real world, inevitably being inverted and actually reversed. Why does little Alice undertake this journey? Simply because he wants another point of view, a reality and a physical and human landscape where everything is reversed, a world in the mirror ..

The novel, which contains numerous interpretations, is commonly seen as a metaphor for the growth process. Wonderland allows Alice to shake off the state of immobility induced by the severe and boring Victorian education, stimulates her curiosity, leads her to look around, to think with hear head, to accept that you can also be wrong and, in any case, discover a new part of yourself, the one that will lead you to review all your previous certainties and create new ones, thanks also to the characters that she meets (Pinco and Panco,the white rabbit, the cheshire cat, the queen, etc.). And this only to remain in a “superficial” reading of the story.

I like to think that perhaps, learning another “logic”, the girl encounters the correct functioning of things, because subverting the rules makes her understand how basically the “game” is direct “the sense” and not the opposite. The famous dialogue with the Cheshire Cat is an example:

Alice: I just wanted to ask you which way I should go!

Cheshire Cat: Well, it all depends on where you want to go …

Alice: Oh, it really doesn’t matter, as long as I can get out of here

Cheshire Cat: So it doesn’t matter which path you take, doesn’t it?

Once again, an existential metaphor of the fact that in order to grow, the path to find cannot be any one but must be one’s own.

But the story, between fantasy and reality, is even more complex. Lewis Carroll is also a great photographer, a forerunner introduced to the art by Oscar Rejlander, one of the pioneers of photography.

For him (who is ultimately a “God” man) photography proves to be an ideal tool for expressing what he called “beauty”: a state of grace, of moral, aesthetic and physical perfection to be sought and found in the arts, of course , but also in mathematical formulas and in the human figure, especially if female, and especially if “innocent”.

In short: over half of the Carroll’s photographs are of girls, who (often photographed naked) subsequently affixed their signature in a corner of the press. Needless to say, this “passion” created him a reputation as a “pedophile”, when instead his goal was to free himself (and free the young models) from the oppressive burden of Victorian symbolism, imagining them more as creatures ” of nature ”rather than as irreproachable bridesmaids.

But Carroll also made portraits for prominent personalities of his time such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron and Alfred Tennyson. He is now considered one of the fathers of modern photography.

But, going back to his very young models, do you know what his favourite model’s name was? Alice Liddell …

And she is the Alice (whose face we know perfectly) that ends up in Wonderland in Carroll’s fantasy. But it is also she who, exactly six months after the trip to Wonderland, napping on an armchair in her living room, wonders what is on the other side of the mirror and, to her great surprise, manages to pass through it and find an answer to his curiosities.

Beyond the mirror Alice will meet talking flowers, characters of the chessboard and very strange animals, as well as all the characters of her favorite nursery rhymes (those typical of the English tradition) such as the absurd twins Tweedledee and Tweedledum and Humpty Dumpty.

But while Alice is busy widening her point of view further by visiting the disturbing landscape that is “on the other side” of the mirror, she does not notice that, firmly and rigidly blocked, in the vicinity of the mirror itself (just where she entered) there is also another boy, who could perhaps benefit greatly from Alice’s help and from her experience in “elsewhere” …

“Tommy” is a Who record. Released in 1969, it is a masterpiece of rock history. A work from which a Ken Russell film will then be made.

Tommy is a boy who witnesses (from behind a mirror …) the murder of his mother’s lover by his father, a British aviator on his return from the front. Tommy’s parents order the child not to say, see and hear anything See me, Feel me, Touch me, Heal me …. it is the song that as leitmotiv runs through the whole opera and that the Who will perform a few months later in Woodstock, definitely entering the legend.

Tommy receives the traumatic order and thus becomes mute, blind and deaf. In practice, it is as if he remained “behind the mirror”, but in an order superimposed and parallel to reality where the absence of logic and the reversal of common sense, which for Alice is populated by funny and paradoxical figures that are somehow “didactic” “, for him becomes an authentic ordeal, exposed as he is to all kinds of violence, and abuse from the” normal “people around him.

But then the ransom occurs: Tommy, traveling through the only magic he can practice, intuition, discovers that he is a fantastic pinball player.

In a short time he defeats anyone else, even the greatest, the world champion, who, amazed, calls him “Pimball Wizard” (pinball wizard) and, addressing the audience (in the song) tries to explain what he feels like to see this boy who “plays with intuition. He is blind, dumb and deaf and is a pinball wizard. He has nothing to distract him but he cannot see the lights, the signals, the colors, the flashes, and he cannot hear the bells and vibrations of the machine. He plays according to the sense of smell, and is never wrong .. ”

Tommy, once rich and famous, will manage to regain normalcy, voice, hearing, sight … only when the mother destroys the mirror, thus allowing him to finally “go out the other side” and, perhaps, to meet over there a pretty girl who, meanwhile (like him, moreover) has become a little bit older …

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

lascia una risposta