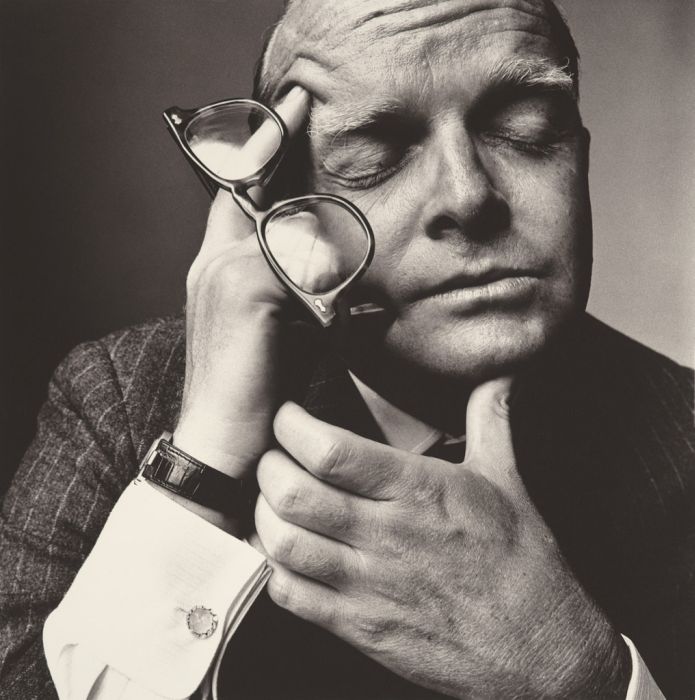

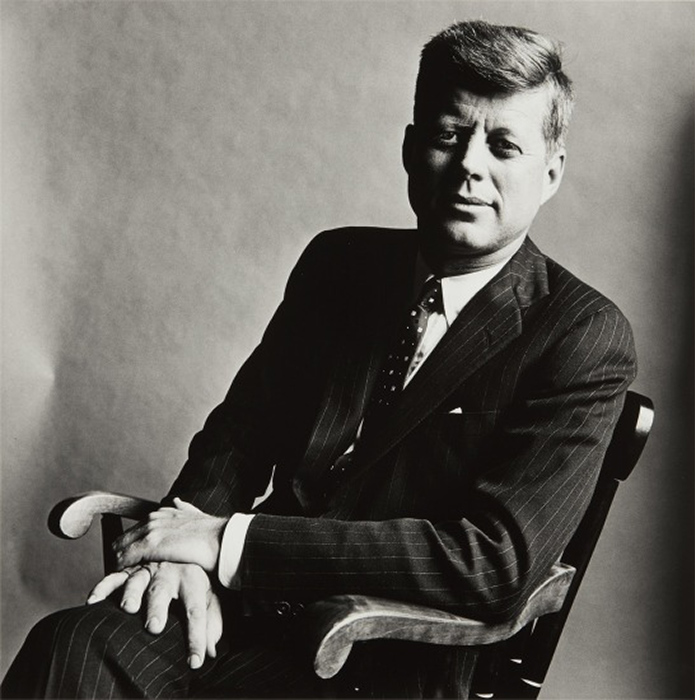

Irving Penn (Plainfield, 1917 – New York, 2009) è stato un fotografo statunitense, fratello maggiore del famoso regista Arthur Penn e universalmente conosciuto per le sue fotografie di moda, ritratto e still life. Dal 1943 comincia a lavorare per “Vogue” e avvia una formidabile serie di ritratti tra i quali quelli di molte celebrità.

English versionLa sua cifra stilistica modifica lo sguardo attraverso il quale si colloca emotivamente la percezione dell’osservatore e permette la lettura di dettagli interiori che avvicinano sensibilmente al mondo interiore del personaggio ritratto. Tutto ciò attraverso una raffinata ma semplice combinazione di soluzioni formali.

Per valorizzare le sedute estemporanee che da un certo momento in poi realizzerà viaggiando intensivamente, crea un piccolo studio fotografico da viaggio, con il quale può fotografare sullo stesso scenario in ogni parte del mondo e in ogni condizione. Nasce così la famosa serie Worlds in a small room (mondi in una piccola stanza), nella quale si alternavano ritratti di personaggi celebri e fotografie di gruppo dove l’etnografia si mescolava alla moda.

Irving Penn amava presentare la figura da ritrarre in forte contrasto con il suo sfondo preferito: una vecchia tenda di teatro trovata a Parigi, dipinta con diffuse nubi grigie, che usò per 60 anni.

In alcune sue immagini i ritratti sono eseguiti disponendo il soggetto da riprendere davanti a due di questi fondali disposti ad angolo. Messi (quasi costretti) in questo angolo, i personaggi ritratti sembrano cedere quasiasi finzione rappresentativa e ci consegnano per intero la loro anima.

“Durante il 1948 ho iniziato a fotografare ritratti in un piccolo spazio d’angolo realizzato con due pannelli messi insieme e il pavimento coperto con un pezzo di moquette vecchia… questo confinamento, sorprendentemente sembrava dare conforto alle persone, calmandole. Le pareti erano una superficie su cui appoggiarsi o spingere contro…”

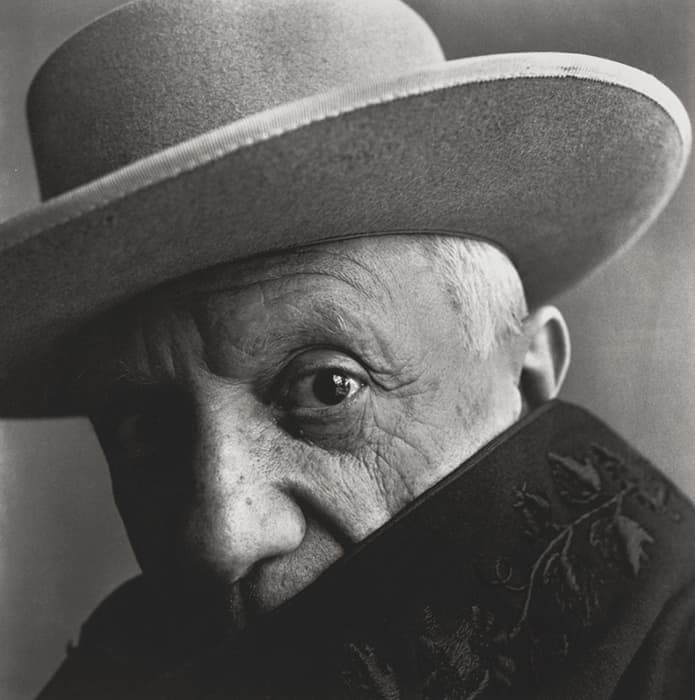

A mio avviso nessuno, comunque, di questi ritratti, pur fantastici, raggiunge la forza espressiva, rilassata e tesissima al tempo stesso, di quello di Marcel Duchamp. Stretto nell’angolo l’artista è vestito di scuro, le tinte lo rendono parte effettiva del fondale. Sul suo viso aleggia l’ombra di un sorriso…impossibile decifrare se di compiacimento oppure di indifesa ammissione di umanità.

Non c’è praticamente più nulla di nuovo che si possa dire su Marcel Duchamp (Blainville-Crevon, 1887 – Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1968).

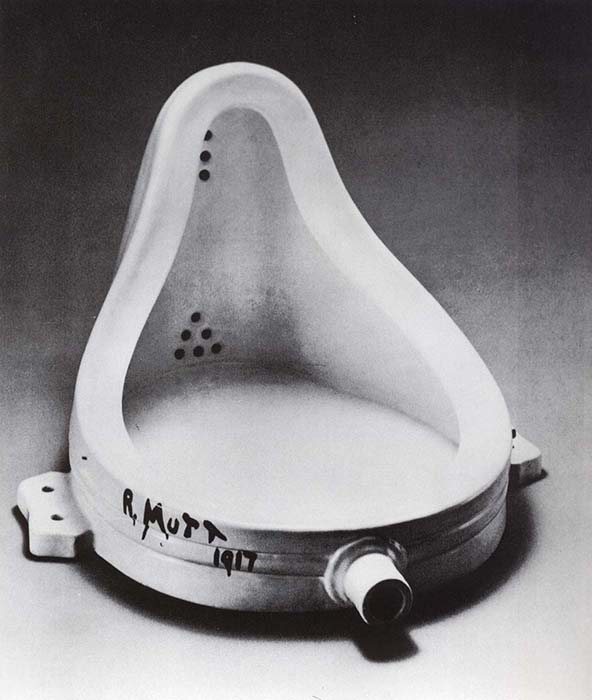

Come è scritto su Wikipedia, parliamo di uno “scultore, pittore, scacchista francese naturalizzato americano che nella sua lunga attività si occupò di pittura (attraversando le correnti del fauvismo e del cubismo), fu animatore del dadaismo e del surrealismo, e diede poi inizio all’arte concettuale, ideando il ready-made e l’assemblaggio.”

Marcel Duchamp è considerato uno fra i più importanti e influenti artisti del XX secolo, e su di lui sono state scritte tonnellate di inchiostro.

Critici, artisti, scrittori, poeti e centinaia di altri intellettuali, ma anche personaggi di altre discipline oppure decisamente senza discipline di riferimento hanno tentato di analizzare il suo lavoro e la sua figura da ogni punto di vista, avventurandosi spesso in teorizzazioni e chiavi interpretative di grande interesse e rilievo ma non di rado dal fantasioso al ridicolo.

Inutilmente: Duchamp è “un’anguilla filosofica”. Più cerchi di prenderlo e più ti scappa. E proprio l’impossibilità di definirlo e di spiegarlo ha sempre contribuito ad affermare e confermare la sua distaccata importanza creativa (poiché smise di fare arte per giocare a scacchi) ed il suo inimitabile senso della riproducibilità (chiunque ha provato a fare dei multipli o delle scatole come le sue senza riuscirci, proprio perché avendo creato il concetto di “ready made”, cioè di cosa “già esistente”, le aveva già fatte lui, senza averle fatte…)

Come afferma Octavio Paz nel suo saggio su Duchamp Apparenza Nuda:

«le tele di Duchamp non raggiungono la cinquantina e furono eseguite in meno di dieci anni: infatti abbandonò la pittura propriamente detta quando aveva appena venticinque anni. Certo, continuò “a dipingere”, ma tutto quello che fece a partire dal 1913 si inserisce nel suo tentativo di sostituire la “pittura-pittura” con la “pittura-idea”. Questa negazione della pittura che egli chiama olfattiva e retinica (puramente visiva) fu l’inizio della sua vera opera. Un’opera senza opere: non ci sono quadri se non il Grande Vetro (il grande ritardo), i ready-mades, alcuni gesti e un lungo silenzio».

Ecco, il Grande Vetro… un’opera alla qual da oltre 80 anni tutti si sforzano di dare un significato ed un’interpretazione…

Ma il vero significato,è proprio nella sua indecifrabilità; dichiara l’artista in un’intervista del ‘64:

«considero quella mia grande pittura su vetro qualcosa che non è necessario guardare per apprezzarla. Questa è una delle idee [che stavano] alla sua base».

In qualche modo, Duchamp delega all’osservatore la possibilità di dare all’opera l’interpretazione che preferisce, dal momento che essa non si presta in alcun modo, volutamente, ad una lettura univoca e universale.

Duchamp poi peggiora in qualche modo la situazione perché nel 1923 dichiara il grande dipinto su lastra di vetro non finito. Questo fa sì che anche la fortuita rottura dell’opera venga considerata da Duchamp come un’ulteriore conferma del ruolo giocato dal caso in tale processo e quindi anche dell’impossibilità di intervenire sul fluire di esso. Il caso appartiene alla realtà, proprio come l’arte…

In Rocky 1 (n.d.R.: 1979, scritto, diretto e interpretato da Sylvester Stallone), il pugile Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone), ammesso alla sfida per il titolo mondiale dei pesi massimi, si inventa un curioso ed efficace metodo di allenamento, molto nazional popolare – nel rispetto del personaggio – fatto di sessioni di pugni ai quarti di bue, ginnastica ai limiti del sopportabile e, infine, di corse sfrenate per i viali di Philadelphia alle prime luci dell’alba.

Nella memoria popolare e cinematografica resta scolpita la scena nella quale Rocky termina la sua corsa salendo freneticamente la scalinata di un museo e si rivolge infine figuratamente al mondo a braccia aperte come a voler reiterare ed affermare la sua sfida, la sua rivolta.

Rocky vincerà l’incontro e darà il via ad una serie interminabile di sequel. Nel secondo episodio la scena si ripete ma stavolta il pugile, ormai campione e celebre, è seguito sulla scalinata da una folla entusiasta composta per lo più da ragazzi che alla fine gli si stringono addosso in pura adorazione.

Il sole che, nel frattempo, fa capolino dalla parte sinistra dei rilievi del museo, sembra provenire da una stanza segreta, posta al limitare della costruzione ma in una qualche profondità simbolica, e crea un lungo riflesso che sottolinea la scena.

Il museo è il Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art dove dal 1954 è conservato il Grande Vetro, che ha, in realtà, un titolo che dice «La Sposa messa a nudo dai suoi Scapoli, anche».

A questa opera Duchamp ha lavorato per circa otto anni, dal 1915 al 1923. Il quadro è formato da due enormi lastre di vetro (277 x 176 cm) che racchiudono lamine di metallo dipinto, polvere, e fili di piombo.

Nel gennaio del 1986 mentre giravo assorto intorno al Grande Vetro sentii un bambino esclamare rivolto al padre : “ Papà!! Nel vetro ci siamo noi !!”

Era vero. Nel Vetro c’ero anch’io. Tutti coloro che si fermano davanti al Grande Vetro e lo guardano sono implacabilmente riflessi ma, e questo è il punto, per il tempo dell’osservazione diventano parte effettiva dell’opera.

Questo era il vero gioco di Duchamp, secondo me: della sua opera, che non è un’opera, nella sua opera e intorno alla sua opera, siamo tutti aggiuntivi fantasmi, siamo illusioni di un’illusione.

Quando uscimmo dal Museo faceva un gran freddo. Dovevamo aspettare almeno un’ora prima della partenza del pulmann che ci avrebbe riportati a New York, così entrammo in una caffetteria per mangiare una fetta di dolce. Dopo un po’ andai alla toilet. Mi accorsi subito che tra l’ingresso dei bagni e quella del vano Uomini le porte formavano un incastro abbastanza improbabile, una ad apertura interna, l’altra interna, in uno spazio molto esiguo.

In pratica mi ritrovai spalmato in un pertugio tra le due porte che mi impediva ogni movimento, orientandomi solo verso il water e precludendomi anche di girarmi. Così mi misi a guardare il gabinetto, i suoi minimi arredi pensati per viaggiatori, per passeggeri e frettolosi consumatori di caffè.

Pensai agli spettatori di un match di Rocky, pensai al Grande Vetro che se ne stava lì ad aspettare riflessi per vivere altre vite, pensai alla vita, al freddo, alle città, al tempo, mi venne da sorridere, mi abbottonai i pantaloni, feci una torsione per uscire da quell’incastro, e magari da altri incastri, e me ne andai.

The work without works

Irving Penn (1917-2009) was an American photographer, older brother of the famous film director Arthur Penn. He is universally known for his fashion, portrait and still life photographs. From 1943 he began working for Vogue and started a formidable series of portraits, including those of many celebrities.

Its stylistic code modifies the look through which the perception of the observer is emotionally placed and allows the reading of interior details that bring us closer to the inner world of the portrayed character. All this through a refined but simple combination of formal solutions.

To enhance the impromptu sessions that from a certain moment onwards he will travel intensively, he creates a small travel photographic studio, with which he can photograph on the same scenario in every part of the world and in all conditions. Thus was born the famous “Worlds in a small room” series, in which portraits of famous people and group photographs alternated where ethnography was mixed with fashion.

Penn loved to present the figure to be portrayed in stark contrast to his favorite background: an old theater curtain found in Paris, painted with diffuse gray clouds, which he used for 60 years. In some of his images the portraits are executed by arranging the subject to be taken in front of two of these backdrops arranged at an angle.

Placed (almost forced) in this corner the portrayed characters seem to give up any representative fiction and give us their whole soul.

“During 1948 I started photographing portraits in a small corner space made with two panels put together and the floor covered with a piece of old carpet… this confinement, surprisingly, seemed to give comfort to people, calming them down. The walls were a surface to lean against or push against … ”

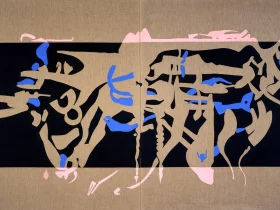

In my opinion, however, none of these portraits achieves the expressive force, relaxed and tense at the same time, of that of Marcel Duchamp. Tight in the corner, the artist is dressed in dark, the colors make it an effective part of the backdrop. On his face hovers the shadow of a smile … impossible to decipher whether of complacency or of defenseless admission of humanity.

There is practically nothing new that can be said about Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

As Wikipedia says we are talking about a ” French naturalized American sculptor, painter, chess player who in his long career worked on painting (crossing the currents of Fauvism and Cubism), was the animator of Dadaism and surrealism, and then began the conceptual art, conceiving the ready-made and the assembly. ” Duchamp is considered one of the most important and influential artists of the twentieth century, and tons of ink have been written on him. Critics, artists, writers, poets and hundreds of other intellectuals, but also characters from other disciplines or decidedly without reference disciplines have attempted to analyze his work and his figure from every point of view, often venturing into theorizations and interpretative keys of great interest and importance, but often from the imaginative to the ridiculous.

Needlessly: Duchamp is a “philosophical eel”. The more you try to catch it, the more it run away. And the impossibility of defining and explaining it has always contributed to affirming and confirming his detached creative importance (since he stopped making art to play chess) and his inimitable sense of reproducibility (any artist has tried to make “multiples” or boxes like him without success, precisely because having created the concept of “ready made”, that is, what “already exists”, he had already made them, without having made them …)

As Octavio Paz states in his essay on Duchamp “Naked appearance”, “Duchamp’s paintings do not reach the number of fifty and were made in less than ten years: in fact, he abandoned the properly so called painting when he was just twenty-five years old. Of course, he continued to “paint”, but everything he did since 1913 is part of his attempt to replace “painting-painting” with “painting-idea”. This denial of the painting which he calls olfactory and retinal (purely visual) was the beginning of his true work. A work without works: there are no paintings except the Great Glass (the great delay), the ready-mades, some gestures and a long silence ».

Here we are, the Great Glass … a work to which for over 80 years everyone has been striving to give meaning and interpretation …

But the real meaning is precisely in its indeciphrability: “I consider that great painting of mine on glass something that it is not necessary to look at to appreciate it. This is one of the ideas [that were] behind it, “says the artist in an interview from ’64. Somehow, Duchamp delegates to the observer the possibility of giving the work the interpretation he prefers, since it does not lend itself in any way, deliberately, to a univocal and universal reading.

Duchamp then “worsens” the situation somewhat because in 1923 he declares the large painting on an “unfinished” glass plate. This also means that the accidental breakdown of the work is considered by Duchamp as further confirmation of the role played by chance in this process and therefore also of the impossibility of intervening on its flow. Chance belongs to reality, just like art …

In “Rocky 1” the boxer Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone), admitted to the challenge for the world heavyweight title, invents a curious and effective very popular training method made of punching sessions at quarter beefs, gymnastics at the limits of the bearable and, finally, of unbridled runs through the avenues of Philadelphia at the first light of dawn. The scene in which Rocky ends his run by frantically climbing the steps of a museum remains sculpted in the popular and cinematographic memory and finally turns figuratively to the world with open arms as if to repeat and affirm his challenge, his revolt.

Rocky will win the match and kick off an endless series of sequels. In the second episode the scene repeats itself but this time the boxer, now champion and famous, is followed on the staircase by an enthusiastic crowd composed mostly of boys who in the end huddle against him in pure adoration.

The sun, meanwhile, peeks out from the left side of the museum’s reliefs, seems to come from a secret room, placed on the edge of the building but in some symbolic depth, and creates a long reflection that underlines the scene.

The museum is the Philadelphia Museum of Modern Art where the Great Glass has been preserved since 1954, which actually has a title that says “The Bride Stripped bare by Her Bachelors, even”.

Duchamp worked on this project for about eight years, from 1915 to 1923. The painting is made up of two huge sheets of glass (277 x 176 cm) which contain painted metal sheets, dust, and lead wires.

In January 1986, while I was wandering around the Big Glass, I heard a child exclaiming to his father: “Dad! We are in the glass !! ”

It was true. I was in the glass as well. All those who stop in front of the Great Glass and look at it are relentlessly reflected but, and this is the point, for the time of observation they become an effective part of the work.

This was Duchamp’s true game, in my opinion: of his work, which is not a work, in his work and around his work, we are all additional ghosts, we are illusions of an illusion.

When we left the museum it was very cold. We had to wait at least an hour before the departure of the bus that would take us back to New York, so we went into a coffee shop to eat a slice of cake.

After a while I went to the toilet. I immediately noticed that between the entrance to the bathrooms and that of the Men compartment the doors formed a rather unlikely interlocking, one with internal opening, the other internal, in a very small space. In practice, I found myself smeared in a gap between the two doors that prevented me from moving, orienting myself only towards the toilet and also precluding me from turning around. So I started looking at the toilet, its minimal furnishings designed for travelers, passengers and hasty coffee consumers. I thought of the spectators of a Rocky match, I thought of the Big Glass that was there waiting for reflexes to live other lives, I thought about life, the cold, the cities, at the time, it made me smile, I buttoned my pants, I did a twist to get out of that joint, and maybe other joints, and I left.

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

lascia una risposta