«La fotografia è un’azione immediata; il disegno una meditazione.

La macchina fotografica è per me un blocco di schizzi, lo strumento dell’intuito e della spontaneità.»

(Henri Cartier-Bresson)

Oltre ad essere universalmente riconosciuto tra i più grandi fotografi del 900, Henri Cartier-Bresson (Chanteloup-en-Brie, 22 agosto 1908 – L’Isle-sur-la-

Questa dell’istante perfetto, dove le cose e i soggetti circostanti si andavano assestando in un equilibrio totale, dove ogni punto di fuga dell’osservazione si trovava esattamente al livello ideale per la composizione, senza che la composizione fosse stata ideata e costruita, era la sua unica ossessione, la sua reale ricerca. Ogni sua immagine lascia attoniti proprio per questa sensazione di assoluto che evoca.

Dal suo canto, l’artista (nel 1962, quando era già celeberrimo) dichiarò:

«In realtà la fotografia di per sé non mi interessa proprio; l’unica cosa che voglio è fissare una frazione di secondo di realtà».

Lui amava la pittura, e alla pittura voleva ritornare, non ha mai spesso di ritenersi un pittore, un disegnatore. Intendeva la fotografia come una forma d’arte, ma soprattutto come un’estensione della pittura. Forse nel tentativo inutile di definirne la grandezza, può entrare solo una parvenza di valutazione, a metà tra l’artistico e lo scientifico e, in buona parte, anche di mistico : lui non aveva bisogno di guardare, lui «vedeva».

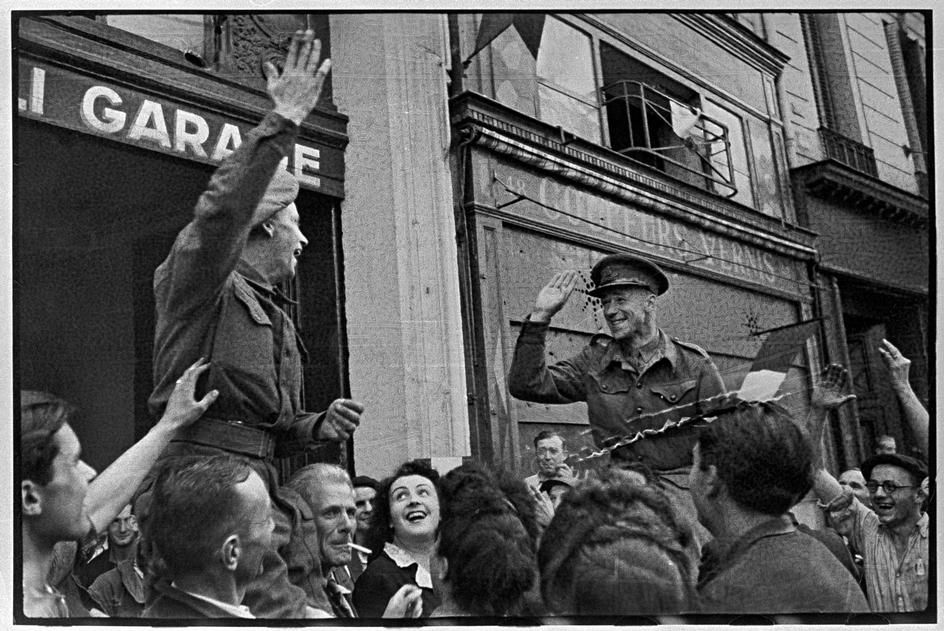

Durante la seconda guerra mondiale era entrato a far parte della resistenza francese. Catturato dai nazisti, riuscì a scappare ed arrivare in tempo per documentare la liberazione di Parigi nel 1944.

Accompagnata quasi costantemente dal mito, la vita di Henri Cartier-Bresson (che è anche tra i fondatori insieme a Robert Capa della celebre agenzia Magnum, 1947 ), è stata lunga e sempre produttiva. Se ne va nel 2004, a 95 anni.

Ancora oggi mi capita di pensare spesso, e di riguardare spesso nei molti cataloghi che ho collezionato visitando le sue mostre un po’ dappertutto, la serie Vedute dalle Torri di Notre-Dame, dove si nasconde un’idea di Parigi che sempre sveglia e riattiva un mio personale mondo emotivo.

Molti anni fa, con una fidanzata che avevo allora ed un gruppo di amici (mai più visti in seguito) di quest’ultima, visitai per la prima volta Parigi. Stranamente, pur avendo già viaggiato più volte in Francia e soprattutto in Bretagna, non mi era ancora capitata l’occasione di vedere Parigi e passarci qualche giorno. Il nostro albergo era a Les Halles e si chiamava D’Angleterre, ma non c’entrava niente con quello dove passò i suoi ultimi giorni Oscar Wilde; era un postaccio squallido e cadente, un edificio polveroso e gigantesco anche se, incastrato tra due palazzi e, risultante (credo) dell’unione tra due o tre altri stabili molto dissimili fra di loro, dalla facciata principale sembrava una palazzina di modeste dimensioni . All’interno ogni piano cambiava volumi e arredamento ad ogni incrocio di corridoi. Ogni piano era, in realtà, un vero labirinto, costellato di segni e richiami sensibili (sporco sui muri, scie sul pavimento di legno, una porta sfondata, una nicchia sul muro) che – come effettivamente pensai di fare – se organizzati in una mappa (i numeri delle stanze erano appena accennati, in angoli misteriosi, sulle porte), avrebbe potuto facilitare molto il ritrovamento delle camere. Però era molto romantico e mi faceva pensare al romanzo parigino di Jack Kerouac, Satori a Parigi.

In quei giorni leggevo Viaggio a Lhasa di Giuseppe Tucci, diario di una spedizione italiana in Tibet negli anni ’20. Poi compravo un sacco di giornali e riviste, e la sera, quando finalmente, molto tardi, andavamo a letto, guardavo con orgoglio poetico la stanza sfattissima, con le brocche di porcellana, con il parquè fuori guida, con le nostre valige buttate per terra (non c’erano altri supporti), con tutto il variopinto caos di vestiti che due ragazzi riescono a creare in giro anche in un paio di giorni, con le scie lasciate dai fiammiferi accesi sul muro sopra il letto da chissà quante generazioni di visitatori, ne respiravo l’assenza globale di comodità e di pulizia e sprofondavo nella mia stessa letteratura, compiacendomi, sentendomi – una volta tanto – in armonia con me stesso, al posto giusto.

Ma dopo qualche giorno i miei compagni risultarono tutti afflitti da improvvisi malesseri, febbre, raffreddori, mal di gola…

Una sera, quando tornammo in albergo dopo la cena in un postaccio tunisino, realizzai che erano proprio tutti, compresa la mia ragazza, fuori uso per il giorno dopo.

Esprimevo preoccupazione e sincero dispiacere ma dentro di me ero molto felice perchè l’idea di girarmi Parigi da solo, in pace, con i miei tempi e il mio modo lentissimo di camminare mi risultava irresistibile.

La mattina dopo feci colazione di buon ora e mi incamminai verso Notre Dame.

Visitai la chiesa e ne ammirai l’immensità, la potenza architettonica… le tonalità conferite alla luce interna dalle vetrate… comprai una guidino… insomma niente di diverso, concettualmente e fisicamente da quanto facevano le valanghe di comitive di turisti che sciamavano da tutte le parti.

Dopo un po’ questo mi sembrò molto deludente e uscii di nuovo. Presi a bighellonare sul lungo Senna in declivio che si apre davanti alla cattedrale, sul Quai de Montebello e sul Quai de la Tournelle, dove da secoli i bouquinistes vendono libri – e talvolta sembra che la loro merce non sia cambiata molto nel tempo.

In maggior parte sono libri francesi di seconda o terza mano, ma alcuni venditori sono specializzati in settori quali il cinema o le vecchie riviste. Altri vendono stampe e cartoline… Notai che qualcuno aveva anche dei fumetti.

Da una distesa di questi «giornaletti», come li ho sempre chiamati, mi attrasse immediatamente una bella edizione cartonata… quando dico mi attrasse intendo quella speciale forma di richiamo che solo l’oggetto libro può esercitare quando stabilisce che è arrivato il tempo giusto e la persona giusta per lui… mi avvicinai, lo sfilai dalla pila e lo rigirai per guardarne la copertina.

Che fosse un qualcosa riguardante Paperino mi era subito sembrato evidente ma non potevo certo pensare di trovarmi tra le mani l’edizione originale (1964), in inglese, di Uncle Scrooge The Phantom of Notre Duck, uscita in Italia il 5 marzo 65 (mio tredicesimo compleanno) col titolo di Zio Paperone e i misteri della cattedrale.

Guardavo la copertina del libro, lo sfogliavo come per cercare qualcosa nascosto tra le pagine, e ogni tanto gettavo uno sguardo alla facciata di Notre Dame, che mi troneggiava alle spalle…

Paperino…Paperone…

Bruce Chatwin dedicò un intero breve saggio alla suggestione che gli veniva evocata fin da bambino dalla parola “Timbuctù, ovverosia da una specie di simbolo letterario (e fonetico) della più assoluta lontananza geografica e mentale, dell’Altrove.

Io posso dire lo stesso. Timbuktu… Zanzibar… l’Alaska… l’altrove mitico, la voglia di scoprire luoghi dove possono ancora celarsi i misteri, è apparsa nella mia vita come profonda fascinazione, come impulso al movimento, alla disaffezione per la realtà prevedibile e troppo sicura, tramite i fumetti, per mezzo di nomi ancor più evocatori quanto abilmente (ma dichiaratamente) truccati, lievemente difformi dall’originale, quanto bastava per prendere le distanze dai generi più seri dell’intrattenimento, garantendosi così l’appartenenza all’universo infantile.

Credo proprio che tutta la mia cultura di base, sia dal versante nozionistico che da quello che riguarda l’attitudine a creare, improvvisare su un tema, lasciar affiorare una suggestione dalle fantasticherie, insomma il bagaglio complessivo di risorse mentali con il quale sono entrato nella vita e grazie al quale faccio spesso la figura dell’uomo colto, mi viene dalla precoce, accanita, costante e capillare lettura (dovrei dire studio, l’unico mai svolto volentieri…) dei fumetti di Paperino, cioè Donald Duck…

Donald Fauntleroy Duck nasce nel 1934 (e non morirà mai) ideato da Walt Disney e realizzato graficamente dal disegnatore Al Taliaferro.

Veste perennemente con un abito blu alla marinara, con i bottoni dorati, e un cappellino che gli caratterizza il viso. Inizialmente fece da spalla a Topolino, ma ben presto Walt Disney si rese conto che il personaggio meritava una testata tutta sua, con delle storie che dovevano vederlo come protagonista assoluto.

E’ un pasticcione, confusionario, dispettoso, irascibile, testardo, pigro, fifone, và sempre incontro ad un mare di guai, complicandosi la vita per una sciocchezza, soprattutto perchè è perseguitato da una tremenda sfortuna. Paperino vive in una casetta con giardino nella città di Duckburg (Paperopoli) e si arrangia a fare mille mestieri dal pompiere al gelataio, dall’ incantatore di serpenti al pescivendolo ecc… Viaggia con una macchinetta rossa e blu in stile Cabriolet targata 313.Così come per Topolino, anche per Paperino esiste l’eterna fidanzata e questa è Paperina (Daisy Duck).

Carl Barks nasce invece nel 1901 in una fattoria nei pressi di Merrill, Oregon, una minuscola cittadina al confine con la California.

Carl, afflitto da una forma di sordità parziale, sviluppa la tendenza ad isolarsi e ad evitare il più possibile il contatto con gli altri e, chiuso per ore nella sua stanzetta, da corpo al suo mondo fantastico disegnando e facendo scarabocchi ovunque. Crescendo farà molti mestieri ma senza mai abbandonare la sua autentica passione, la sua via di fuga dalla realtà: il disegno

Nel 1935, viene assunto da Disney, che aveva creato da un anno il personaggio di Donald Duck, Lavorando intensamente Barks di lì a pochi anni modifica l’aspetto di Paperino e gli confeziona una personalità molto caratterizzata, buffonesca e irascibile insieme, ma anche uno spirito avventuroso che lo porta a viaggiare e a esplorare il mondo, affrontando mille avventure.

Ma nel 1947 Barks ha un’altra intuizione vincente: ispirato dal vecchio avaro Ebenezer Scrooge di Dickens, inventa lo zio di Paperino, che si chiama – per l’appunto – Scrooge, in Italia Paperon de Paperoni, il papero, oppure l’uomo, più ricco del mondo.

I propri averi li tiene nel suo deposito che sovrasta la città di Paperopoli come un simbolo e un ammonimento. Avaro fino all’esasperazione, nevrotico e ansioso, Paperone nel tempo travalica il proprio stesso personaggio, la propria stessa origine, che non viene più collocata ma infinitamente accennata, riposizionata in epoche favolose della conquista del West e di altri luoghi memorabili da dove sempre si parte e raramente si lasciano ricordi raccontabili. Inutile dirgli che il denaro non dà la felicità, infatti il dollaro e i fantastiliardi sono molto di più: il suo destino.

Barks, (che come Cartier-Bresson morirà ben oltre i 90 anni, nel 2000), come sollecitato dalla curiosa coppia che adesso può gestire, e già da tempo incurante della realtà o della verosimiglianza storica, andrà collocando sempre più spesso le avventure di Paperone e Paperino in diverse epoche della storia e della mitologia, ma – influenzato dalla successiva passione per la narrativa noir e misteriosa, nel tentativo di arricchire sempre la gamma delle sue possibilità narrative – pescherà a piene mani per i suoi soggetti anche dal romanzo e dal feuilleton popolare.

La storia di “Zio Paperone e i misteri della cattedrale” è ispirata infatti in modo evidentissimo sia al celebre romanzo di Victor Hugo, “Notre Dame de Paris “(1831), di cui la cattedrale di Paperopoli è quasi una copia, sia all’altrettanto celebre “Il fantasma dell’opera” (1910), romanzo di Gaston Leroux.

Alla ricerca di un piffero sparito, in un’atmosfera rarefatta come difficilmente un fumetto riesce a creare, attraverso le inquietanti penombre e i mille segreti e trabocchetti della cattedrale, Zio Paperone, Paperino e i nipoti Qui, Quo e Qua, trovano, dopo molte difficoltà e grazie al manuale delle Giovani marmotte, il misterioso inquilino di Notre Duck (Notre Paper nella versione italiana) .

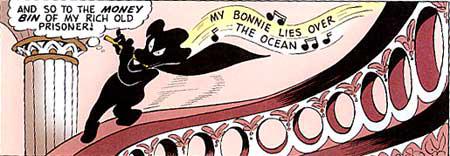

Il fantasma ammantato di nero, che volteggia tra scale e colonne cantando My Bonnie lies Over the Ocea” (una traditional song a suo tempo interpretata anche dai Beatles) tiene lungamente in scacc la famiglia dei paperi, depredando Paperone di una intera cariolata di monete, che utilizza nella finalizzazione del suo hobby: costruire in scala ridotta un modello della cattedrale solo, appunto, con delle monetine.

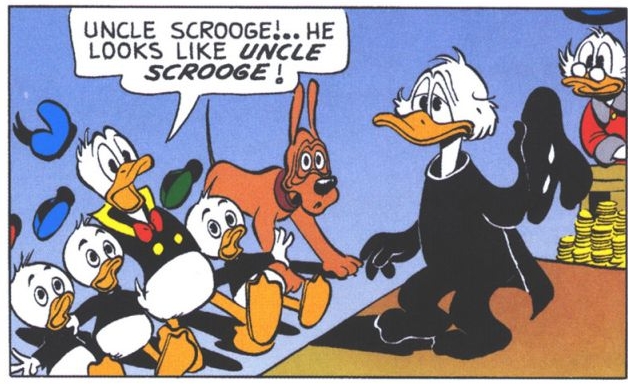

Geniale è il colpo di scena finale quando il ladro mostra il suo vero volto, praticamente identico a quello dello Zio Paperone.

Ecco, se Cartier-Bresson fosse stato presente avrebbe chiaramente riconosciuto l’essenza del Momento Decisivo e non avrebbe resistito alla tentazione di fotografare i due paperi, identici, l’uno specularmente all’altro, riconoscendo allo stesso tempo a Carl Barks la sua stessa qualità di Sguardo.

E così, con il mio prezioso giornaletto tra le mani, mi girai e, dopo pochi minuti, con grande decisione entrai nuovamente in Notre Dame. Naturalmente non c’era più nessuno, nessun turista, nessun prete, nessuna anziana signora coperta di nero, nessun francese, pio o solo abituato a frequentare le chiese… no: nessuno.

Venni colto da un brivido di autentica esaltazione, come forse non avevo mai registrato in vita mia, e come forse non ho mai più sperimentato in seguito…

Avevo l’immensa cattedrale tutta per me, avevo tutto il tempo del mondo, tutte le potenzialità e le possibilità spalancate davanti a me…..e quel che è più, e che non è facile descrivere, spiegare, vivevo solamente e chiaramente nei colori, nelle tinte magistrali che le vetrate gettavano intorno trasformando la luce esterna e le complicazioni del mondo in prospettive del pensiero…..

Poi mi fermai ancora – maledetta abitudine ! – a riflettere: «Possibile che sperimento tutto ciò, che riesco a vedere e sentire Notre Dame così presente fisicamente e così altrove, ma non qui, non in un altro posto, la riesco a sentire come forza, come disegno ed esperienza della realtà scollegandola dalla realtà, rendendola solo un momento nella vita non mia, ma dell’universo? Possibile che possa essere così contento di avere qualcosa che non riuscirò mai a spiegare ma che resterà per sempre mia e mi tornerà in mente quando avrò bisogno, ogni volta che avrò bisogno, di capire tutto l’insieme senza capirne nessun particolare, senza averne la pretesa, di provare ad esplorare l’altrove senza dover andare chissàdove, senza partire, scappare? e… possibile che debba questa illuminazione… questo satori… ad un fumetto, e, in definitiva, ad un gruppo di paperi… ?».

Mi sedetti all’estremità di una delle lunghe panche. Due o tre file avanti a me sedeva qualcun altro. Mi sembrava di sentirlo respirare.

Quando ero molto piccolo mio padre, tornando a casa, mi diceva spesso: «Ehi… Paperino… che fai?»

Mi alzai e mi diressi in fretta all’uscita. Avevo delle monetine in tasca e mi sembrò ancor più che saggio, utile, lasciarle tutte nel recipiente per le offerte votive ad un Santo, dall’aria simpatica ma poco adatta, a mio avviso, ad un fumetto.

The decisive moment

«Photography is an immediate action; drawing a meditation.

The camera is for me a sketch pad, the instrument of intuition and spontaneity.»

(Henri Cartier-Bresson)

In addition to being universally recognized among the greatest photographers of the 20th century, Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) played a fundamental role in the theorization of the act of photographing, translated among other things in the famous definition of the “decisive moment” which is also the title of his most famous book (1952).

This of the perfect instant, where the surrounding things and subjects were settling in a total balance, where every vanishing point of the observation was exactly at the ideal level for the composition, without the composition having been conceived and built, was the his only obsession, his real quest. Each of his images leaves you astonished precisely by this feeling of absolute that evokes.

For his part, the artist (in 1962, when he was already very famous) declared “In reality, photography itself does not interest me at all; the only thing I want is to fix a split second of reality ». He loved painting, and he wanted to return to painting, he never often considers himself a painter, a draftsman. He intended photography as a form of art, but above all as an extension of painting.

Perhaps in the useless attempt to define its greatness, only a semblance of evaluation can enter, halfway between the artistic and the scientific and, in large part, also of the mystical: he did not need to look, “he saw”

During the Second World War he had joined the French resistance. Captured by the Nazis, he managed to escape and arrive in time to document the liberation of Paris in 1944.

Accompanied almost constantly by myth, the life of Henri Cartier-Bresson (who is also one of the founders together with Robert Capa of the famous Magnum agency), was long and always productive. He leaves in 2004, at the age of 95.

Even today I often think, and often look back in the many catalogs that I have collected while visiting his exhibitions almost everywhere, the series “views from the Towers of Notre-Dame”, where an idea of Paris that always wakes up is hidden. and reactivates my personal emotional world.

Many years ago, with a girlfriend I had then and a group of friends (never seen since) of the latter, I visited Paris for the first time. Strangely, despite having already traveled several times in France and especially in Brittany, I had not yet had the opportunity to see Paris and spend a few days there.

Our hotel was in Les Halles and was called “d’Angleterre” but it had nothing to do with the one where Oscar Wilde spent his last days. It was a shabby and dilapidated place, a dusty and gigantic building even if, wedged between two buildings and, resulting (I think) from the union between two or three other very dissimilar buildings, from the main facade it looked like a small building. Inside, each floor changed volumes and furnishings at each intersection of corridors. Each floor was, in reality, a real labyrinth, studded with signs and sensitive references (dirt on the walls, trails on the wooden floor, a broken door, a niche in the wall) which – as I actually thought I would do – if organized in a map (the room numbers were barely mentioned, in mysterious corners, on the doors), it could have greatly facilitated the finding of the rooms.

But it was very romantic and made me think of Jack Kerouac’s Parisian novel, “Satori in Paris.” In those days I was reading Giuseppe Tucci’s “Journey to Lhasa”, the diary of an Italian expedition to Tibet in the 1920s. Then I bought a lot of newspapers and magazines, and in the evening, when finally, very late, we went to bed, I looked with poetic pride at the very unmade room, with the porcelain jugs, with the parquet out of the way, with our suitcases thrown on the ground (there were no other supports), with all the colorful chaos of clothes that two boys manage to create around even in a couple of days, with the trails left by the matches lit on the wall above the bed by who knows how many generations of visitors, I breathed in the total absence of comfort and cleanliness and sank into my own literature, delighting, feeling – for once – in harmony with myself, in the right place.

But after a few days my companions were all afflicted with sudden illness, fever, colds, sore throat … One evening, when we returned to the hotel after dinner in a Tunisian place, I realized that everyone, including my girlfriend, was out of order for the next day.

I expressed concern and sincere displeasure but inside I was very happy because the idea of walking around Paris alone, in peace, at my own pace and my very slow way of walking was irresistible.

The next morning I had an early breakfast and set off for Notre Dame.

I visited the church and admired its immensity, its architectural power … the shades given to the interior light by the windows … I bought a guidebook … in short, nothing different, conceptually and physically from what the avalanches of groups of tourists were doing who swarmed from all set off.

After a while this seemed very disappointing and I went out again. I took to loitering on the long sloping Seine that opens up in front of the cathedral, on the Quai de Montebello and the Quai de la Tournelle, where bouquinists have been selling books for centuries – and sometimes it seems that their wares haven’t changed much over time. Most are second- or third-hand French books, but some sellers specialize in sectors such as cinema or old magazines. Others sell prints and postcards… I noticed that some also had comics.

From an expanse of these “magazines”, as I have always called them, a beautiful hardcover edition immediately attracted me … when I say attracted me I mean that special form of appeal that only the book object can exercise when it establishes that the right time has come and the right person for him … I walked over, took it off the pile and turned it over to look at the cover.

That it was something about Donald Duck immediately seemed obvious to me but I certainly couldn’t think of finding in my hands the original edition (1964), in English, of Uncle Scrooge “The Phantom of Notre Duck”, released in Italy on 5 March 65 (my thirteenth birthday) with the title of “Uncle Scrooge and the mysteries of the cathedral”.

I looked at the cover of the book, leafed through it as if looking for something hidden among the pages, and every now and then I would glance at the facade of Notre Dame, which towered behind me …

Donald … Scrooge …

Bruce Chatwin dedicated an entire short essay to the suggestion that was evoked to him as a child by the word “Timbuktu” that is a kind of literary (and phonetic) symbol of the most absolute geographical and mental distance, of the Elsewhere.

I can say the same. Timbuktu … Zanzibar … Alaska … the mythical elsewhere, the desire to discover places where mysteries can still be hidden, appeared in my life as a profound fascination, as an impulse to movement, to the disaffection for predictable and too safe reality, through comics, by means of names even more evocative as well as skilfully (but admittedly) made up, slightly different from the original, just enough to distance themselves from the more serious genres of entertainment, thus guaranteeing belonging to the childhood universe.

I really believe that all my basic culture, both from the notional side and from what concerns the aptitude to create, improvise on a theme, let a suggestion emerge from daydreams, in short, the overall baggage of mental resources with which I entered the life and thanks to which I often play the figure of the “cultured” man, it comes to me from the precocious, relentless, constant and capillary reading (I should say study, the only one ever willingly done …) of Donald Duck’s comics, that is Donald Duck …

Donald Fauntleroy Duck was born in 1934 (and will never die) conceived by Walt Disney and graphically created by the designer Al Taliaferro.

He always wears a navy blue dress with golden buttons and a hat that characterizes his face. Initially he supported Mickey Mouse, but Walt Disney soon realized that the character deserved a head of his own, with stories that had to see him as the absolute protagonist. He is a bungler, confused, spiteful, short-tempered, stubborn, lazy, cowardly, he always goes into a sea of troubles, complicating his life for a trifle, especially because he is haunted by tremendous misfortune. Donald lives in a small house with a garden in the city of Duckburg (Duckburg) and arranges to do a thousand jobs from the firefighter to the ice cream maker, from the snake charmer to the fishmonger, etc … Travel with a red and blue “Cabriolet” style machine. 313 Just as for Mickey, Donald also has an Carl Barks was born in 1901 on a farm near Merrill, Oregon, a tiny town on the border with California.

Carl, afflicted by a form of partial deafness, develops a tendency to isolate himself and to avoid contact with others as much as possible and, closed for hours in his small room, gives body to his fantastic world by drawing and scribbling everywhere. Growing up he will do many jobs but without ever abandoning his authentic passion, his escape from reality: drawing

In 1935, he was hired by Disney, who had created the character of Donald Duck for a year, Working intensely Barks changed the appearance of Donald Duck in a few years and gave him a very characterized personality, at the same time funny and irascible, but also a adventurous spirit that leads him to travel and explore the world, facing a thousand adventures.

But in 1947 Barks has another winning intuition: inspired by Dickens’ old miser Ebenezer Scrooge he invents Donald Duck’s uncle, who is called – precisely – Scrooge, in Italy Paperon de Scrooge.

The duck, or man, richest in the world.

He keeps his belongings in his warehouse overlooking the city of Duckburg as a symbol and a warning. Stingy to exasperation, neurotic and anxious, Scrooge over time goes beyond his own character, his own origin, which is no longer placed but infinitely hinted at, repositioned in the fabulous epochs of the conquest of the West and other memorable places from where it has always been part and rarely are recountable memories left. Needless to tell him that money does not give happiness, in fact the dollar and the billions are much more: his destiny.

Barks, (who like Cartier-Bresson will die well over 90, in 2000), as urged by the curious couple who can now manage, and for some time now oblivious to reality or historical verisimilitude, will increasingly place the adventures of Scrooge and Donald Duck in different eras of history and mythology, but – influenced by the subsequent passion for noir and mysterious fiction, in an attempt to always enrich the range of his narrative possibilities – he will draw heavily for his subjects also from the novel and the popular feuilleton.

The story of “Uncle Scrooge and the mysteries of the cathedral” is clearly inspired both by the famous novel by Victor Hugo, “Notre Dame de Paris” (1831), of which the Duckburg cathedral is almost a copy, and by the equally famous “The Phantom of the Opera” (1910), novel by Gaston Leroux.

In search of a disappeared fife, in a rarefied atmosphere as hardly a comic can create, through the disturbing shadows and the thousand secrets and pitfalls of the cathedral, Uncle Scrooge, Donald Duck and the nephews Qui, Quo and Qua, find, after many difficulties and thanks to the Young Marmots manual, the mysterious tenant of Notre Duck (Notre Paper in the Italian version).

The “ghost” cloaked in black, who twirls between stairs and columns singing “My Bonnie lies Over the Ocean” (a traditional song also interpreted by the Beatles at the time) keeps the duck family in check for a long time, robbing Scrooge of a whole bunch of coins, which he uses in the finalization of his hobby: to build a small-scale model of the cathedral only with coins.

The final twist is brilliant when the thief shows his real face, virtually identical to that of Uncle Scrooge.

Here, if Cartier-Bresson had been present, he would have clearly recognized the essence of the Decisive Moment and would not have resisted the temptation to photograph the two identical ducks, one mirroring the other, while at the same time recognizing Carl Barks as his Look quality.

And so, with my precious comic in my hands, I turned around and, after a few minutes, with great decision, I entered Notre Dame again. Of course there was no one left, no tourists, no priests, no old lady covered in black, no French, pious or just accustomed to going to churches … no one.

I was seized by a thrill of authentic exaltation, as perhaps I had never recorded in my life, and as perhaps I have never experienced since …

I had the immense cathedral all to myself, I had all the time in the world, all the potentials and possibilities opened up in front of me … ..and what’s more, and which is not easy to describe, to explain, I lived only and clearly in the colors , in the masterful colors that the windows cast around, transforming the external light and the complications of the world into perspectives of thought … ..

Then I stopped again – damn habit! – to reflect: “Is it possible that I experience all this, that I can see and feel Notre Dame so physically present and so elsewhere, but not here, not in another place, I can feel it as a strength, as a design and experience of reality by disconnecting it from reality, making it just a moment in life not mine, but of the universe? possible that I can be so happy to have something that I will never be able to explain but that will always remain mine and will come back to me when I need, whenever I need, to understand everything without understanding any particular, without having the claim, to try to explore elsewhere without having to go who knows where, without leaving, running away? is…. Is it possible that he owes this enlightenment… this satori… to a comic, and ultimately to a group of ducks…? ”

I sat down at the end of one of the long benches. Two or three rows ahead of me sat someone else. I seemed to hear him breathe.

When I was a child my father, coming home, often said to me: “Hey .. Paperino … what are you doing?”

I got up and walked quickly to the exit. I had some coins in my pocket and it seemed even more than wise, useful, to leave them all in the container for votive offerings to a saint, with a nice air but not very suitable, in my opinion, for a comics character.

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

lascia una risposta