“Nelle fotografie a colori c’è già tutto. Una foto in bianco e nero invece è come un’illustrazione parziale della realtà. Chi la guarda, deve ricostruirla attraverso la propria memoria che è sempre a colori, assimilandola a poco a poco. C’è quindi un’interazione molto forte tra l’immagine e chi la guarda. La foto in bianco e nero può essere interiorizzata molto di più di una foto a colori, che è un prodotto praticamente finito.”

(Sebastião Salgado)

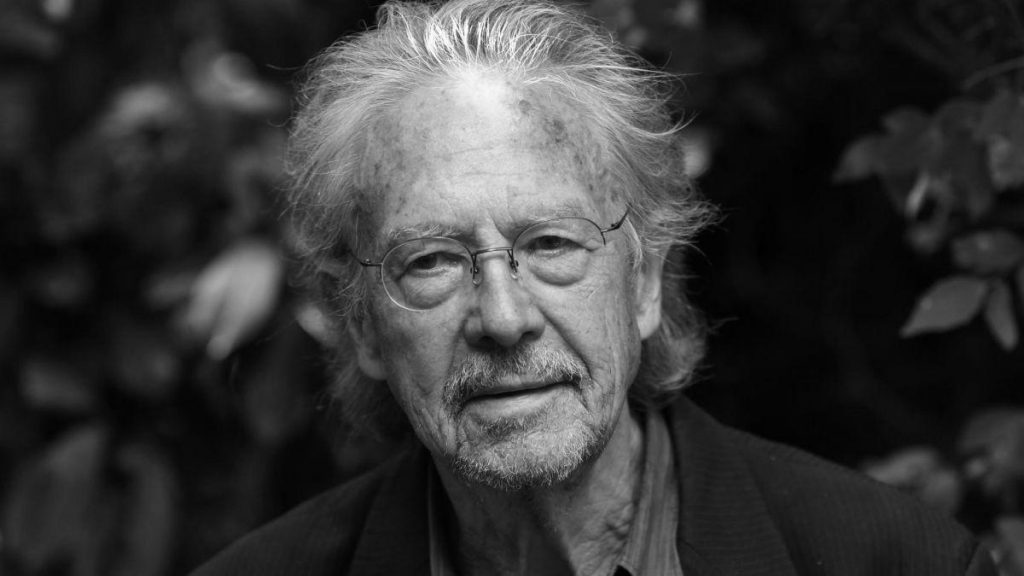

Peter Handke, scrittore austriaco di origini slovene, nato nel 1942, è diventato famoso molto presto, anche se in modo non particolarmente positivo.

All’inizio della sua carriera si propone, infatti, come provocatore, innovatore, iconoclasta e promotore di un teatro mobile, molto vivo, dove le figure degli attori e del pubblico spesso si rovesciano nei ruoli interagendo e contaminando la stessa messinscena.

Questo e altro suscita scandali (Insulti al pubblico), discussioni a non finire di natura morale e concettuale quando tocca con violenza le tradizioni e il senso della famiglia (Infelicità senza desideri), e – nell’insieme – lo si considera come un “giovane arrabbiato”, semmai questa definizione, presa molto in prestito, abbia un senso.

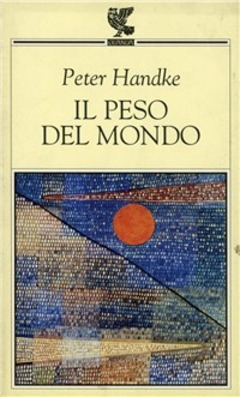

E’ autore di un notevole numero di romanzi, commedie, e poesie che più sperimentali non si può (Il mondo interno dell’esterno dell’interno), strani diari, collezioni di appunti e pseudo narrazioni in forma di saggio. Raggiunge una prosa densa ma molto meditata, dove i personaggi sono indagati nella loro essenza comportamentale piuttosto che raccontati (La Donna Mancina), non rinunciando, comunque, mai al senso profondo di un movimento ambiguo, nelle storie, appena percettibile, a scatti e a sensazioni.

Ma quello che lo caratterizza è una dimensione sacrale, sempre lirica, della scrittura, un amore vertiginoso per la realtà dello scrittore che vive pienamente questa essenza di ruolo, e non ne può impersonare nessun’altra.

Dimensione che trasmette ai personaggi, i quali sembrano quasi sempre narrare la sua vita, in termini e tempi lentissimi, studiati senza rimedio, più assenti che presenti, giacchè di loro si presenta la mancanza piuttosto che la partecipazione, quasi simbolica, agli eventi raccontati (Lento ritorno a casa).

Io l’ho incontrato (metaforicamente) un giorno d’estate del 1978 all’edicola della stazione di Forlì o di Cesena, quando aspettando un diretto per tornare a Bologna, guardai i libri esposti e decisi di acquistare proprio Infelicità senza desideri, la storia di sua madre, spietata e ai limiti del rancore, ma pervasa di un tetro, profondissimo senso di amore. Stile scarno, periodi brevi, poche pagine.

Questo mi è successo con Handke: per molto tempo ho letto tutti i suoi libri senza quasi capire perchè lo facevo. Si era creata una coazione a ripetere, a leggere, spesso nemmeno apprezzando le storie.

Poi ho capito cosa mi succedeva leggendolo: ne avevo bisogno, mi rappresentava, tutta questa sicura indeterminatezza questa lirica modernità narrata con un passo antico, era simbolicamente il segno di quanto avrei voluto-dovuto essere o diventare, proprio stimolandomi nell’assenza di chiavi fornite, a cercarne di mie proprie.

Peter Handke, che un paio di anni fa (fra varie polemiche) ha vinto il Premio Nobel per la letteratura, l’ho lasciato per strada già da molto tempo, proprio perchè nel mio processo di cambiamento a un certo punto ho realizzato di non essere più la persona che aveva bisogno di leggerlo.

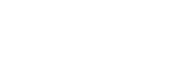

Ma non potrò mai dimenticare quanto libri come Nei colori del giorno (dedicato alla montagna Sainte Victoire e a Cézanne), una specie di cronaca di un viaggio di scoperta in solitaria, o Il peso del Mondo (uno struggente diario per piccoli appunti, spesso aforismi) mi abbiano accompagnato, reso più agile mentalmente, più poeta e meno poetico nel mio sentire artistico.

Come dimenticare questa frase:

“Talvolta quando giro il cucchiaino nel tè, e frantumo lo zucchero, mamma si muove con me?”

Prima mi sembrava solo una bella frase, molto triste, e ora che sono orfano mi sembra un’illuminazione di verità totale…

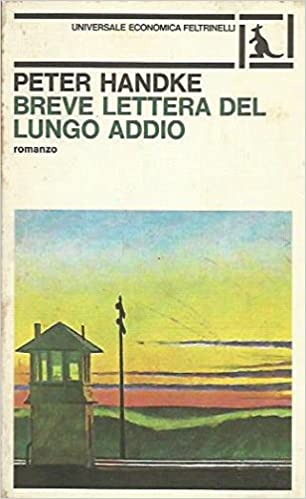

E poi era arrivata la Breve lettera del lungo addio, una storia d’amore e di addio scritta da Handke alla vigilia della separazione dalla prima moglie. La cifra più personale della narrazione però, più che il riferimento autobiografico al proprio matrimonio, sta nel movimento, nel viaggio, negli spostamenti tra Europa e America, nel ripetuto allontanarsi e riavvicinarsi dei protagonisti.

La breve lettera, in fondo, è già stata scritta, il lungo addio deve essere celebrato, e avviene compiutamente con l’apparizione di John Ford che l’autore, come per realizzare un sogno adolescenziale, fa incontrare al suo protagonista. Nel finale la coppia fa una passeggiata col regista americano e gli racconta la propria vicenda, ovvero la storia del libro.

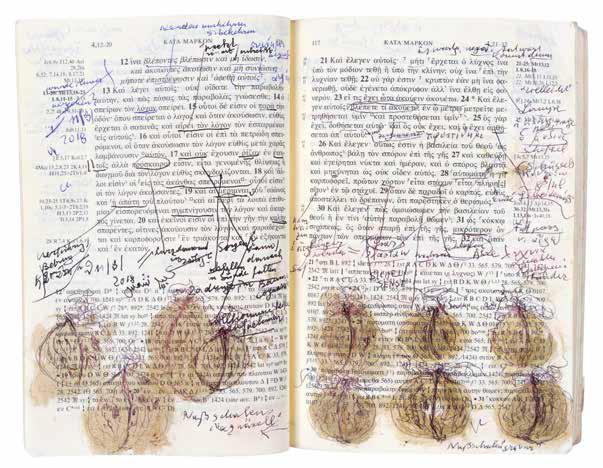

Qui appaiono l’America, il viaggio, la solitudine, gli orizzonti che si avvicinano e si allontanano come i personaggi, il passaggio narrativo da una letteratura statica a un raccontare sè stessi nel movimento, già come se una macchina da presa ci desse il ritmo, il senso del tempo e delle immagini… il cinema… il cinema di Wim Wenders…

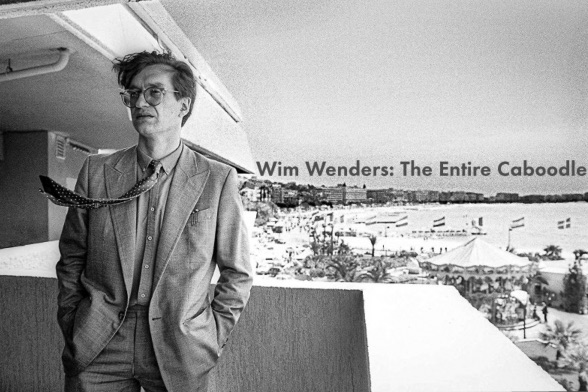

Wim Wenders ( (Düsseldorf, 14 agosto 1945) è un regista, sceneggiatore e produttore cinematografico tedesco, esponente di primo piano del Nuovo cinema tedesco.

Lo scrittore austriaco e il regista tedesco si sono conosciuti nel 1966 e da allora hanno lavorato insieme tante volte: i libri dell’uno si sono trasformati nei film dell’altro.

Infatti, il tema del viaggio caratterizza la prima e consistente parte della produzione di Wenders: e Alice nelle città, girato in parte negli Stati Uniti, che racconta l’amicizia tra un giovane reporter e una bambina, sembra riprendere in qualche modo tutte le suggestioni della Breve Lettera.

Mi ricordo la prima volta che ho visto il film, insieme a mio fratello, il 1° luglio del 1986 a Roma. Faceva così caldo che tenemmo per tutto il tempo la finestra grande aperta, e il rumore incessante del traffico di Via Tuscolana sembrava quasi fare parte della storia, aggiungere una colonna sonora ideale alle immagini.

Alice nelle città, insieme a Falso movimento e Nel corso del tempo, forma un nucleo di tre film dove sembra non succedere nulla e succede tutto, li si guarda con occhi inevitabilmente spostati sul versante della poesia, così come questo modo itinerante, silenzioso, quasi per appunti, di fare cinema, è suggerito dalla scrittura precisa, lenta, incalzante e lirica di Handke, che qualche anno dopo appare anche figuratamente mentre scrive (con penna stilografica nera) il testo de Il cielo sopra Berlino nei vari passaggi del film.

Nel 1975 dopo aver diretto L’amico americano, con Bruno Ganz e Dennis Hopper (da un romanzo di Patricia Highsmith), si trasferisce negli USA per circa quattro anni.

Le pellicole di questo periodo (Lampi sull’acqua – Nick’s Movie, Hammett – Indagine a Chinatown e Lo stato delle cose) determinano una forma di stasi poetica, i lampi che Wenders raccoglie dalla letteratura che ama e che lo condiziona, pur filtrati dalla grande passeggiata per il continente americano, lo lasciano ancora più desideroso di ulteriori riflessioni sulla lentezza del mondo e sulla inconoscibilità del reale.

Ne è prova : Lo stato delle Cose, girato in Portogallo e a Los Angeles, che racconta la vicenda di un regista rimasto senza soldi e pellicola per continuare a riprendere.

Wenders vince sempre più premi e riconoscimenti e va avanti nel tempo e nel suo vagabondare, alternando visioni americane (Paris, Texas) a profondità e narrazioni europee (Il cielo sopra Berlino, Lisbon Story), ma è sempre più interessato a mettere in atto esperimenti cinematografici e culturali, documentari di colore e musica che cerchino di capire come funziona il cuore di un artista, e così arriva Buena Vista Social Club...

Ma fotografare, come fare dei films, significa “scrivere con la luce”…

Sebastião Ribeiro Salgado Júnior (Aimorés, Brasile, 1944) è un fotografo brasiliano che, attualmente, vive a Parigi. Di lui si sa tutto perché è probabilmente il fotografo più famoso del mondo. Si sa anche che senza la spinta decisiva della moglia Lélia Wanick Salgado “sarebbe stato un bancario”…

Fu lei a insistere perché il giovane Salgado lasciasse il posto fisso. Si sa anche che il personaggio non tende ad un’introversione pensosa e spesso malinconica, solo parzialmente redenta dalle immagini che realizza, spesso disperate, selvagge e tragiche.

La sua traccia sembra essere proprio quella di un costante approccio formale, profondissimo ma del tutto lontano dal sensazionale.

I personaggi che fotografa attirano lo sguardo perchè sembrano creature mitiche, eroi e attori di un’ epica d’altri tempi, ma in realtà sono semplicemente operai, coltivatori di canna da zucchero, fuggiaschi, gruppi di madri e bambini, masse in movimento, segni di trasformazione catartica ma quasi involontaria.

E la chiave della potenza di ogni sua foto sta proprio in questa assenza di significati ulteriori, solo realtà, realtà estrema, dolorosa e drammatica, priva di consolazione, ma del tutto concreta, visibile, respirabile.

Aveva già lavorato sedici anni per la mitica agenzia Magnum quando decide dicreare, insieme alla moglie, Amazonas Images, una struttura autonoma completamente dedicata al suo lavoro, ovvero reportage di impianto umanitario e sociale. Inizia quella che sente essere la sua avventura intima e devastante, il senso della missione che lo anima internamente e dalla quale non c’è scampo.

Lo stesso modo che ha di intraprendere i viaggi, le caratteristiche delle riprese (spesso in ambiente molto difficile) dimostrano che vive quello che devevivere, quella dimensione che trascende paura, fatica e sogni ad occhi aperti. E che dentro però brucia come un fuoco quasi impossibile da spegnere ma anche da sopportare all’infinito.

Infatti, dopo aver lavorato a Other Americas, documentando il lavoro nelle campagne, e per altri lunghi anni a La mano dell’Uomo (il lavoro che lo rende celebre in tutto il mondo, avendo dato vita ad una grande mostra itinerante e ad un inusuale libro di oltre 400 pagine di grandi dimensioni), arriva un crollo, un periodo di crisi.

Forse perché avendo visto troppo, lo scarto tra il documentare e il fare doveva essere riempito. Così, con un amico ingegnere forestale, pianta due milioni e 300 mila alberi e trasforma un’area in via di sparizione in Riserva Naturale Privata.

Fondano l’Istituto Terra, nel 1998, che prosegue la sua missione con la riforestazione di circa 7.600 ettari e corsi di specializzazione per giovani agronomi. Dal 1993 al 1999 Salgado lavora sul tema delle migrazioni umane (Migrations)e realizza poi Genesis, il risultato di un lavoro durato otto anni.

“In 30 spedizioni – a piedi, in aereo leggero, in barca e persino con il pallone aerostatico, attraverso temperature estreme e in situazioni talvolta molto pericolose – va alla riscoperta di montagne, deserti, oceani, animali e popolazioni che si sono finora sottratti al contatto con la cosiddetta società civile.”

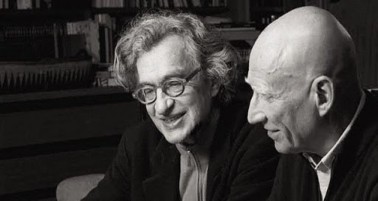

La mostra Genesi è stata esposta in molte città italiane, contribuendo non poco all’aumento esponenziale della sua fama. Fama che però supera ogni confine, ottenendo anche l’attenzione totale di tutti coloro che normalmente non si interessano di fotografia, quando avviene l’incontro con Wenders. Si dice che tutto abbia inizio da una cena a Parigi.

Il feeling è immediato, i due artisti si mettono subito a lavorare insieme. Si rivelerà un’ottima idea, visto che il documentario Il sale della terra, premio speciale della sezione Un certain regard al Festival di Cannes e premiato anche dal pubblico al Festival di San Sebastian, sarà campione di incassi, e uno dei documentari più visti in Italia negli ultimi quindici anni, con oltre 250.000 spettatori.

Il sale della terra è un documentario che si trasforma in una narrazione specifica, il ritratto creativo di un grande fotografo, che esplora la natura intima, tragica ed epica del mondo attraverso le visioni catturate con sprezzo del pericolo e tecnica superlativa dei protagonisti della battaglia per la vita e per la sopravvivenza sulla terra.

Il film, girato da Ribeiro Salgado ( suo figlio) e da Wenders, sempre in un magnifico bianco e nero (cifra, ben argomentata, del suo modo di intendere la rappresentazione fotografica), documenta il lavoro compiuto in 26 paesi, rivolgendo con rabbia e compassione lo sguardo al destino sociale degli espropriati e degli sfruttati come atto di sfida e denuncia a chi produce e prospera attraverso questo sfruttamento.

“I registi lo seguono nella sua erranza, nella ricerca di ciò che genera dolore e disuguaglianze, amore e fraternità, e autorizza ciascuno a prendersi cura di tutto quanto limiti l’uomo nell’esercizio della libertà. Salgado racconta la sua vita e quella della sua famiglia in maniera pudica, in punta di fotografia. Da un lato le sue immagini sono tra le più sublimi che un uomo abbia mai dedicato alla bellezza della terra, e di contro esprimono una denuncia profonda della politica con la quale la rapacità del potere oltraggia da secoli l’intera umanità.”

Ma è anche un’epica in se stessa, dove il mezzo fotografico viene celebrato proprio in quella che è la sua conseguenza, cioè il cinema, e a farlo è un regista come Wenders che è anche e appassionatamente fotografo narrativo…

Wenders, ha detto che la prima metà della sua vita appartiene al cinema, mentre la seconda metà alla fotografia e ha aggiunto:

“Non mi sono mai considerato un vero narratore. Mi sono sempre visto come qualcuno che si preoccupa di immagini, che siano quadri, disegni, o fotografie.”

E infatti mi viene in mente un libro fotografico che Wenders pubblicò nel 1993, Una Volta, composto di 60 immagini introdotte da brevi narrazioni, tutte che – come nel classico impianto del racconto fiabesco o del cantastorie – iniziano con la frase: Una volta.

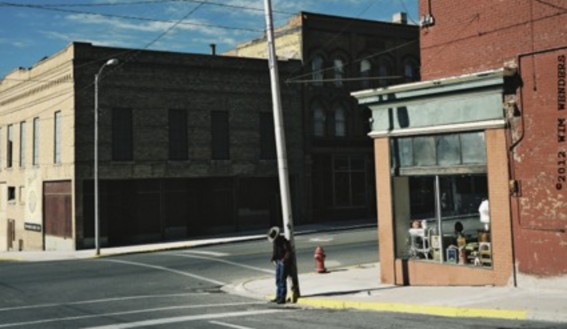

Si tratta di brevi istantanee narrative, reliquie del presente o rovine del nostro tempo come certi interni di locali lungo le highways, o aerei nel deserto con le ali smontate oppure i drive-in e motel abbandonati.

Queste storie sono uno specchio mobile che inquadra la realtà ponendone in dubbio la consistenza formale, la compresenza del gesto umano e i contorni (le cornici) che, racchiudendo la foto che segue, ne rallentano la progressione verso il caos.

Ecco: la fotografia è un tentativo di rallentare la marcia del caos, di dare un senso all’altrimenti inarrestabile disordine delle cose e degli uomini, come sa bene Salgado che, nel mentre fotografa gli inferni terrestri che penetra, sa che il suo, in fondo, è l’unico tentativo praticabile che l’artista possa intraprendere per salvare l’uomo.

Penso che a Salgado siano piaciuti i foto-racconti di Una Volta, così vuoti e così pieni al tempo stesso. E penso che a Peter Handke sia certamente piaciuto ritrovarsi in uno delle storie del libro:

“Una volta sono andato a trovare il mio amico Peter Handke a New York. Stava scrivendo il romanzo “Lento ritorno a casa”. In quel periodo viveva in un albergo sul versante est di Central Park, ritirato come un monaco. Anche la mia breve presenza lo ha, credo, più che altro irritato. Ho fatto una foto alla sua scrivania, una della nostra passeggiata, “sparata” dal fianco, e un’altra della sua figura che si allontanava, dopo che ci eravamo separati. Solo più tardi, quando ho letto “Lento ritorno a casa”, ho capito quell’oppressione, che, nel voltarmi indietro, avevo colto sulle sue spalle.”

Quel peso, il peso del mondo…

The weight of the world

“In color photographs, everything is already there. A black and white photo, on the other hand, is like a partial illustration of reality. Whoever looks at it must reconstruct it through his own memory which is always in color, assimilating it little by little. There is therefore a very strong interaction between the image and the viewer. The black and white photo can be internalized much more than a color photo, which is a practically finished product.”

(S. Salgado)

Peter Handke, an Austrian writer of Slovenian origins, born in 1942, became famous very soon, albeit in a not particularly positive way. In fact, at the beginning of his career he proposed himself as a provocateur, innovator, iconoclast and promoter of a very lively mobile theater, where the figures of the actors and the public often overturn their roles interacting and contaminating the same staging.

He provokes scandals (Insults to the public), endless discussions of a moral and conceptual nature when he violently touches traditions and the sense of family (Unhappiness without desires), and – on the whole – one considers him as an angry “young man”, if this much borrowed definition makes sense.

He is the author of a considerable number of novels, comedies, and poems that cannot be more experimental (The internal world of the exterior of the interior), strange diaries, collections of notes and pseudo-narratives in the form of essays. It reaches a dense but very meditated prose, where the characters are investigated in their behavioral essence rather than told (La Donna Mancina), never giving up, however, the profound sense of an ambiguous movement, in the stories, barely perceptible, jerky and sensations.

But what characterizes him is a sacred dimension, always lyrical, of writing, a dizzying love for the reality of the writer who fully lives this essence of role, and cannot impersonate any other. Dimension that he transmits to the characters, who almost always seem to narrate his life, in very slow terms and times, studied without remedy, more absent than present, since they are lacking rather than participating, almost symbolic, in the events told ( Slow return home).

I met him (metaphorically) one summer day in 1978 at the newsstand of the Forlì or Cesena station, when waiting for a direct return to Bologna, I looked at the books on display and decided to buy my own Unhappiness without desires, the story of his mother, ruthless and on the verge of rancor, but pervaded by a gloomy, very deep sense of love. Lean style, short periods, few pages.

This happened to me with Handke: for a long time I read all of his books almost without understanding why I did it. There was a compulsion to repeat, to read, often not even appreciating the stories.

Then I understood what was happening to me reading it: I needed it, it represented me, all of it this certain indeterminacy, this lyrical modernity narrated with an ancient passage, was symbolically the sign of what I wanted-should have been or become, precisely by stimulating me in the absence of supplied keys, to look for my own.

Peter Handke, who a couple of years ago (amid various controversies) won the Nobel Prize for literature, I left him on the street for a long time, precisely because in my process of change at a certain point I realized that I was not plus the person who needed to read it.

But I will never forget how many books like In the colors of the day (dedicated to the Sainte Victoire mountain and Cézanne), a kind of chronicle of a solo voyage of discovery, or The weight of the world (a poignant diary for small notes, often aphorisms) they accompanied me, made me more agile mentally, more poet and less poetic in my artistic feeling. How can we forget this sentence: “Sometimes when I turn the spoon in the tea, and I crush the sugar, Mom moves with me”?

That first seemed to me just a beautiful sentence, very sad, and now that I am an orphan it seems to me an illumination of total truth …

And then came the “Short letter of the long goodbye”, a story of love and farewell written by Handke on the eve of separation from his first wife. The most personal figure of the narrative, however, rather than the autobiographical reference to one’s marriage, lies in the movement, in the journey, in the movements between Europe and America, in the repeated distancing and getting closer of the protagonists.

The short letter, after all, has already been written, the long goodbye must be celebrated, and it takes place completely with the appearance of John Ford whom the author, as if to realize a teenage dream, brings his protagonist to meet. In the end, the couple takes a walk with the American director and tells him their story, or the story of the book.

Here appear America, travel, loneliness, horizons that approach and move away like the characters, the narrative passage from a static literature to a narration of oneself in movement, already as if a camera gave us the rhythm, the sense of time and images … cinema … Wim Wenders’ cinema …

Wim Wenders (1945), is a German director, screenwriter and film producer, leading exponent of the New German cinema.

The Austrian writer and the German director met in 1966 and have worked together many times since then: the books of one have turned into the films of the other.

In fact, the theme of the journey characterizes the first and substantial part of Wenders’ production: and Alice in the cities, shot partly in the United States, which tells of the friendship between a young reporter and a little girl, seems to somehow take up all the suggestions of the Short Letter.

I remember the first time I watched the film, together with my brother, on 1 July 1986 in Rome. It was so hot that we kept the big window open all the time, and the incessant noise of the traffic on Via Tuscolana almost seemed to be part of the story, adding an ideal soundtrack to the images.

Alice in the cities is a part of a nucleus of three films where nothing seems to happen and everything happens, you look at them with eyes inevitably shifted to the side of poetry, as well as this “itinerant”, silent way , almost for notes, to make films, is suggested by the precise, slow, pressing and lyrical writing of Handke, who a few years later also appears figuratively while writing (with black fountain pen) the text of “The sky above Berlin” in the various passages of the film.

In 1975 after directing L’amico americano, with Bruno Ganz and Dennis Hopper (from a novel by Patricia Highsmith), he moved to the USA for about four years.

The films of this period (Lightnings on the water – Nick’s Movie, Hammett – Investigation in Chinatown, and The state of things determine a form of poetic stasis, the lightnings that Wenders collects from the literature he loves and that conditions him, even if filtered by the great walk around the American continent, leave him even more eager for further reflections on the slowness of the world and the unknowability of reality. Proof of this is: The State of Things, shot in Portugal and Los Angeles, which tells the story of a director who has run out of money and film to continue shooting.

Wenders wins more and more prizes and awards and goes on in time and in his wandering, alternating American visions (Paris, Texas) with European depths and narratives (The sky above Berlin, Lisbon Story), but he is increasingly interested in carrying out cultural experiments and, documentaries of color and music that try to understand how the heart of an artist works, and so comes Buena Vista Social Club …

But photographing, like making films, means “writing by light”.

Sebastião Ribeiro Salgado Júnior (1944) is a Brazilian photographer who currently lives

in Paris. Everything is known about him because he is probably the most famous photographer in the world. We also know that without the decisive push of his wife Lélia “he would have been a banker” …

It was she who insisted that young Salgado leave his permanent position. It is also known that the character does not tend to a pensive and often introversion melancholy, only partially redeemed by the images she creates, often desperate, wild and tragic. His trace seems to be precisely that of a constant formal approach, very deep but completely far from the sensational.

The characters he photographs attract the eye because they look like mythical creatures, heroes and actors of an epic of yesteryear, but in reality they are simply workers, sugar cane growers, fugitives, groups of mothers and children, masses in movement, signs of cathartic but almost involuntary transformation.

And the key to the power of each of his photos lies precisely in this absence of further meanings, only reality, extreme reality, painful and dramatic, without consolation, but completely concrete, visible, breathable.

He had already worked for sixteen years for the legendary Magnum agency when he decided to create, together with his wife, Amazonas Images, an autonomous structure completely dedicated to his work, that is reportage of a humanitarian and social system. What he feels is his intimate and devastating adventure begins, the sense of mission that animates him internally and from which there is no escape.

The same way he travels, the characteristics of the shooting (often in a very difficult environment) show that he lives what he has to live, that dimension that transcends fear, fatigue and daydreams. And inside, however, it burns like a fire that is almost impossible to put out but also to endure indefinitely.

In fact, after having worked in Other Americas, documenting the work in the countryside, and for other long years in Man’s Hand (the work that makes him famous all over the world, having given life to a great traveling exhibition and an unusual book of over 400 large pages), comes a collapse, a period of crisis.

Perhaps because having seen too much, the gap between documenting and doing had to be filled. Thus, with a friend, a forest engineer, he plants two million and 300 thousand trees and transforms an area in the process of disappearing into a Private Nature Reserve. They founded the “Earth Institute” in 1998, which continues its mission with the reforestation of about 7,600 hectares and specialization courses for young agronomists. From 1993 to 1999 Salgado worked on the theme of human migration (Migrations) and then created Genesis, the result of a work that lasted eight years.

“In 30 expeditions – on foot, by light plane, by boat and even by balloon, through extreme temperatures and in sometimes very dangerous situations – he goes to the rediscovery of mountains, deserts, oceans, animals and populations that have so far escaped the contact with the so-called civil society ”.

The “Genesis” exhibition has been exhibited in many Italian cities, contributing not a little to the exponential increase in his fame. Fame that, however, goes beyond all boundaries, also obtaining the total attention of all those who are not normally interested in photography, when the meeting with Wenders takes place. It is said that it all starts with a dinner in Paris.

The feeling is immediate, the two artists immediately start working together. It will prove to be an excellent idea, given that the documentary “The salt of the earth”, special prize of the “Un certain regard” section at the Cannes Film Festival and also awarded by the public at the San Sebastian Film Festival, will be a box office most viewed documentaries in Italy in the last fifteen years, with over 250,000 spectators.

The Salt of the Earth is a documentary that turns into a specific narrative, the creative portrait of a great photographer, which explores the intimate, tragic and epic nature of the world through the visions captured with contempt of danger and superlative technique of the protagonists of the battle for life and for survival on earth.

The film, shot by Ribeiro Salgado (his son) and by Wenders always in a magnificent black and white (well-argued figure of his way of understanding photographic representation), documents the work done in 26 countries, addressing with anger and compassion looking at the social destiny of the dispossessed and exploited as an act of defiance and denunciation of those who produce and prosper through this exploitation.

“The directors follow him in his wandering, in the search for what generates pain and inequalities, love and fraternity, and authorizes everyone to take care of everything that limits man in the exercise of freedom. Salgado tells about his life and that of on the one hand his images are among the most sublime a man has ever dedicated to the beauty of the earth, and on the other hand they express a profound denunciation of the politics with which the rapacity of power outrages from centuries the whole of humanity.”

But it is also an epic in itself, where the photographic medium is celebrated precisely in what is its consequence, that is cinema, and to do so is a director like Wenders who is also and passionately a narrative photographer …

Wenders, said that the first half of his life belongs to cinema, while the second half to photography and added:

“I have never considered myself a true storyteller. I have always seen myself as someone who cares about images, whether they are paintings. , drawings, or photographs.”

And in fact I am reminded of a photographic book that Wenders published in 1993, Una Volta, composed of 60 images introduced by short narratives, all of which – as in the classic fairy tale or storyteller setup – begin with the phrase: Once. These are short narrative snapshots, relics of the present or ruins of our time such as certain interiors of clubs along the highways, or planes in the desert with dismantled wings or drive-ins and abandoned motels.

These stories are a moving mirror that frames reality by questioning its formal consistency, the coexistence of the human gesture and the outlines (the frames) which, by enclosing the following photo, slow down its progression towards chaos.

Well: photography is an attempt to slow down the march of chaos, to make sense of the otherwise unstoppable disorder of things and men, as Sebastiao Salgado while photographing the terrestrial hells he penetrates, knows that his, after all, it is the only viable attempt that the artist can undertake to save man.

I think Salgado liked the photo-stories of Once Upon a Time, so empty and so full at the same time. And I think Peter Handke certainly enjoyed finding himself in one of the stories in the book:

“I once visited my friend Peter Handke in New York. He was writing the novel “Slow Homecoming”. At that time he lived in a hotel on the east side of Central Park, retired as a monk. Even my brief presence has, I think, more than anything else irritated. I took a picture at his desk, one of our walk, “shot” from the side, and another of his figure moving away, after we had separated. Only later, when I read “Slow homecoming”, did I understand that oppression, which, in turning back, I had caught on his shoulders.”

That weight, the weight of the world …

Marco Bucchieri (Roma, 1952) è uno scrittore, poeta visivo e fotografo, attivo sulla scena artistica fin dagli anni ’70. Il suo lavoro si concentra su simbolismo e allegoria, attraverso la realizzazione di mostre, installazioni di poesia visiva, immagini di valenza concettuale, e libri. Attualmente abita in provincia di Bologna, dopo aver vissuto in molte città italiane, a Londra e a New York.

lascia una risposta